Barena Bianca (Fabio Cavallari, b. 1992, and Pietro Consolandi, b. 1991) is a collective that formed in the summer of 2018, as an activist group in the Venetian Lagoon, striving to bring to light many of its ecological and sociological issues, adopting the Barena (typical Venetian salt marsh, essential to the survival of the city) as its emblem. The artists’ work mimics nature, it seeks to emerge in every situation and become visible. Likewise, the fragility and destruction of the natural environments are becoming more clearly visible, increasingly impossible to ignore. Barena Bianca’s work mostly happens in public spaces and formalizes in hybrid collaborative actions, installations and happenings communicated mainly through video. Their work happened and was shown in various circumstances, both informal and institutional, among which the Scottish Pavilion of the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale, V-A-C Foundation and La Serra dei Giardini in Venice, and a solo show in London, at the Imperial College’s Center for Languages, Culture and Communication.

Benedetta d’Ettorre: Barena Bianca is made of two people working together, I am interested in the collaborative aspect of your collective. Were you trained as artists? How does your training and background influence your work?

Barena Bianca: Fabio has a background in art education and graphics, Pietro in contemporary history and political theory. We found that what we studied was limiting in the sense that our disciplines did not have much agency in the world, we wanted to say something, do something. For example we wanted to change relationships between the art world and people. We also had curiosity to find means to formalise research and activities outside of disciplinary boundaries so we trained as artists, specialising in Visual Arts at IUAV in Venice. We share our political activism and we are able to marry ideas and practice in the work that we do together, combining our different ways of thinking and acting. For example the project Muevete Muevete Barena, a didactic happening with 60 kids, was thought to change the institutional relationship with kids. We did not invite them as the recipient of caring responsibilities, to keep them busy while their parents work, but rather as a force of creative production and mutual learning: we also learn a lot from kids.

BD: Many projects and artists’ careers have started with collectives but most of them die out after a while. Collaboration under one umbrella collective presupposes trust and slower processes, including conflicts resolution and giving feedback on each other’s work. Your work has a sense of urgency and responsiveness, I would like to ask you what has brought you together? Was this mode of working brought about as a response to something?

BB: Many collectives in Italy work together because of the sectorial specificity of their skills, to share workloads and have more time to practice. Most of the time artists need to work with other people that are experts in other things, for example scientists or makers, when they approach a new medium. Working as an artist is not yet a fully legitimized profession, most of us as young artists need to have other part-time jobs to survive. In our other life, Pietro worked as a tourist guide in Venice and Fabio is a chef. Time is an important resource, you must collaborate, share skill and expertise if you want to dedicate time to your practice, otherwise you’d have to give up a lot of time to other ways of earning a living. We are very compassionate to each other’s needs and struggles and we support each others practice by working together. Our getting together as a collective was also a response to our desire of staying in Venice after graduation. Whilst this may seem like a personal problem, we realised it’s more of an eco-systemic problem: the city has a problem with people’s retention, not just students but inhabitants as well. Local people, the residents of Venice, have struggled to stay in the city which has changed rapidly in the last 50 years to accommodate mass tourism that eventually turned the city into an hostile environment to resident forms of life. The residents eventually are getting pushed out. At the same time, many students come here to train at prestigious Universities which fill the city with innovative ideas and research, but after graduation we lack an infrastructural support for the settlement of young people and the growth of fresh thought. So the work of our collective is a response, on one hand, to our own struggle to remain in the city but on the other, it is a response to the struggle of many other people who love this place but live on the fine, precarious, line between benefitting from the tourist industry and the detriment that it brings to the economy, ecology and life-style of the city. Such topics are urgent and well known, yet often are not acted upon. This is why we had to develop another layer of collaboration: working closely with people who have our same goals. We were lucky to find an amazing number of determined allies, among which especially local association We Are Here Venice, with whom we kept working and exchanging ideas and knowledge throughout these last few years.

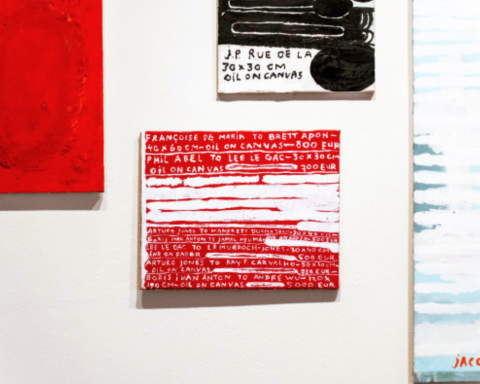

Courtesy Barena Bianca

BD: What does Italy offer and what is lacking in terms of support to the activity of young artists in contemporary art?

BB: Being an artist in Italy is not a job. The commercial private market has always been predominant here, so if you can sell your work you are a professional artist, but if you don’t manage that or if the nature of your practice is not easily sellable, you are not. The market exists only to support artists that are already established, but how do you get to be “established” without the possibility to develop an early career? That’s why people work together, they don’t have the resources to work in another way, but they can’t afford to dedicate themselves full-time to a non-remunerated practice. We lack accessible spaces for exhibitions, studio space and opportunities. All of these things eventually delegitimize your practice. This is an issue that we see everywhere in the artworld, but in particular here it took an eco-systemic form. You need nourishment to support artists, you need to facilitate life in the city, support the public’s creative interests and consumption which eventually feed each other materially and immaterially. Living often abroad, we got to know several virtuous examples of such support, where young artists have opportunities to apply for grants, residencies and to get an affordable studio and so on, this is grounded on a very simple premise: to have art, to produce culture, the artist job has to be legitimated and sustained. Historically Venice was one of the leaders and great example of sustaining artists’ livelihoods and practices: here it was initiated one of the first modern examples of artists in residence programme thanks to the material and philosophical inheritance from Duchess Felicita Bevilacqua La Masa. She gifted the city with her residency palace, to be transformed into a place for young artists to practice freely with residencies and studios. The organisation had many challenges and its administration falls now under the remit of the local authority. This means that real long-term planning is a challenge, when a different mayor’s mandate can dictate a different programme and limit artistic freedom. On the other hand, Venice is famous for its Bienniale, the very first modern example of such an event. While the biennale does good by reopening abandoned spaces and refurbishing them, these spaces are opened only with the aim to be used during the biennale, there is no longer term planning and they are not really accessible to the local people. Talking about Venice as a system of support to the arts and the lagoon as a system of support to sustain people’s life works very well because it can bring together the two realities. Venice does not support emerging, local artistic practices, while it tries to become a stage only for international, top-down programmes that do not engage with the life of the lagoon and at the same time.

BD: The basis of your work is the collaboration between the two of you, but most of your projects widen this collaboration and include other people and organisations. How do these collaborations happen? What do they enable?

BB: We work together but we believe we are only one node of the network. We do relational work, we don’t want to insularly look at things, we produce works aiming at political agency and activation. Muevete Muevete Barena gave us the opportunity to learn with the kids and exist in their reality, as a new generation of prospective inhabitants of the city. As a student you struggle to connect with real people here but we actually discovered that they (10 years-olds from a local elementary school) know a lot about the lagoon’s ecosystem and they have a complex ecological activist vision. When you do a workshop with 60 kids, they have families who are linked to other people and it’s easier to create a snowball effect to impact a lot of people. When the workshop finishes we gift them something, hoping that the object can reactivate the memory of the experience, opening up the space for conversations and sharing. Most of the time we collaborate with lots of different people, hosting institutions, scientists and other people so that we can learn from them and respond to places and contexts from within, and not by parachuting ourselves in different situations. We like to bring forward the network ‘behind the scenes’ of our work because it makes it alive and it’s the very raison d’être of what we do.

BD: What was your very first project? How was it initiated?

BB: Insurrezione Antimimentica Lagunare (Lagoonar Anti-mimetic Insurrection) was our first project, a performative attempt to turn ourselves into a barena (salt marsh). It was that time when we did not know whether we could stay practicing in Venice: we wanted to do something about lives in the city and their survival. The presence of salt marshes is key to the ecosystem as they host different flora and fauna species that are unique to that environment. The erosion and subsequent decline of salt marshes in the lagoon mirrors the decline of people living in the city. We felt a closeness to the salt marshes as we thought that, in a way, we were not really feeling welcome anymore here. If we need to re-think ‘life’ in the lagoon we need to think of all forms of life. We needed a symbol that showed the intricate network of interdependencies of the ecosystem, and we chose the salt marshes: from aerial photos of the lagoon we extracted a pattern that we printed on shirts. In this way, we wore a sort of dysfunctional mimetic uniform in the human environment adopting an aesthetics that made us evident. In the natural environment we would blend but on the Bridge of Sighs we would stand out, showing the paradox that’s behind the history.

BD: In the last exhibition Atensión! at Imperial College London you used data to show the lagoon’s erosion. We read these works today in light of the climate change, and I understood your manifestos as a call to arms to ‘protect’ the lagoon. In relation to geologic eras, the lagoon was supposed to be a moment in time. It continues to exist only thanks to human intervention, which has already affected and deviated the course of nature. What do you think about this?

BB: Venice was born as a refuge for the populations around the coast during the barbaric invasion. Basically every other city in the world was born in hospitable places, the lagoon, which was more like a swamp at the time, attracted the first people exactly because it was not a great place to be in, with the hope that they would not be followed there. The nature of human intervention from the beginning until the Napoleonic conquest was that of trying to understand how to cohabit with the lagoon. Keeping the lagoon healthy was the baseline for building a flourishing civilisation. Everything was thought so that it could be adapted to the lagoon from the hydrodynamics, the digging of the canals the shape of the boats, while now we do the contrary, thinking how the lagoon can be bent to the needs of the market-driven economy. This is the reason why for example the old maps of Venice highlight the islands, they were important and part of the ecosystem, while now they are almost invisible with most of the maps centred on tourists’ attractions. Yes, the lagoon formed relatively recently and if the rivers were not artificially deviated, it would have become another part of land. Similarly, if another big, ‘catastrophic’ natural event would have happened, it could have become part of the sea. The lagoon is an ever-changing ecosystem, the point is not to stop its evolution but rather, as they did in the past, adapt and evolve with it. The lockdown showed this very clearly, nature adapted very swiftly. For example, little egrets and black-winged stilts returned quickly to nest on the bricole, the mooring posts, something that they have not done for years. With the lift of lockdown, many people noticed it and they started to get close to take a photo for their social media, unfortunately this scared away the adults, hindering the process to continue.

All the infrastructural work that has been done to favour Venice’s adaptation to the global economy, was made without any consideration of the lagoon’s ecology and hydrodynamics. We should not only protect Venice and the lagoon from the outside but from what’s happening inside. The posters were not really a call to arms to protect the lagoon because we don’t really need to protect it… they were called atensión (attention in the Venetian dialect), something inspired by Antoni Muntadas’ “warning: perception requires involvement”. One needs to be involved with the lagoon, ‘involved’ as engaging with it and being surrounded by it. It’s a call to enhance our attention, and consider as well local dynamics of the lagoon that are a threat to its survival. With the posters we use a graphic, advertising-inspired, language to be exhibited in one of the few green spaces of Venice, they are colourful 1m x 1.5m posters with big words on it that say things like “Less 70% of the residents in the XXI century”. They were the basis of a performance, where our friend and colleague Ettore Garbellotto carried the posters around on carts shouting “Atensión!”, people would generally encourage and cheer us up. Those were exactly the days when the last art Biennale opened and local people are annoyed by the sudden surge of fancy tourists. The one about residents is a catchy poster because all people living in Venice notice that residents have left the city, as they realise that high-tides are becoming more frequent: depopulation and acqua alta are perhaps the most evident causes of the ongoing ecologic and sociologic catastrophe, they’re literally at our doorsteps.

The other two posters deal with more invisible issues, the erosion of the lagoon and the capacity of absorbing carbon, that are not on people’s doorstep. The basis for any work that involves care and conservation is that you need to pay attention. When you are flying over Venice to see the makeup of the lagoon, or you can see certain things only from a boat, you can’t see them in Venice unless you make an effort. The political message is that if cruises and other big ships can’t go through the canal in the middle of the city, we only need to build another canal, a little bit more distant. This is not solving the problem but it’s just sweeping things under the rug, actually it’s making things worse because you are hiding it from people and causing more damage to the lagoon. The posters were lines of colours to bring attention to underly overlooked facets of the lagoon such as people, salt marshes and their fauna. For local people, seeing something about their city different from the, often disconnected, art exhibited at the biennale, was really engaging even though we communicated with a contemporary art rather than activist language. We adopted this guerrilla strategy of using a different language from the one of the protests to address the same themes and actually widen the reach of the message.

BD: What artists and practices influence your work?

BB: Contemporary artists and lecturers at IUAV such as Antoni Muntadas, Alberto Garutti, Rene Gabri, Elena Mazzi and many others have of course shaped and informed our practice, both as artists and teachers. In particular, thinking about how art can exist in the public space, the process of creation that exists between the work itself and the public. Our vision is to create work engaging with the present public and conceive the work in such a way that it will be able to engage with the future public inhabiting the public space. A work that inspired us deeply as a metaphor is the Wrapped Reichstag by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. It took 25 years for them to realise the project, their determination in pursuing a vision is an ideal that needs to inspire us every day. We take the ephemerality that imbues the strong symbolism of the work as an invite for artists to insist and persist. There is a lot to do to create ecosystemic conscience and awareness. It’s important to insist. For this reason, we are also inspired by those informal groups, co-operatives and organisations in the lagoon that resist and protect local knowledge and ways of life, ranging from fishermen and farmers to glass blowers and boat makers, getting to local rebels and children.

BD: The novel coronavirus has affected the world globally in terms of being a public health crisis, it has impacted negatively on the economy and we still need to understand the social and cultural impacts. On the other hand, with the lockdowns in place and interruption of human activity, we’ve seen the natural environment flourishing everywhere. Many newspapers have titled “nature is taking back Venice”, do you think we can really learn something from this moment?

BB: The coronavirus has shown that we are exposing the most fragile parts of our system to potential shocks. Frédéric Neyrat’s “The Biopolitics of Catastrophe” and Ulrich Beck’s “Risk Society”, on which the former is based, explain how catastrophic events affect everyone, but inevitably damage those who live in most precarious conditions. With policies that detriment social welfare and safety nets, the question is whether to safeguard the population or maintain the GDP, which in turn is obviously not distributed equally. Similarly to the pandemic and contemporary economics, the causes and effects of the pandemic are non-local: this makes it hard to link them, and easy to bring acts of relief where effects strike while maintaining intact the causes of the problem. Resilience urges us to fix the immediate problem, without developing a critical understanding of what has produced the catastrophe. With such a high rate of back-to-back catastrophes, we should be finally getting to grasp such elusive interconnections, hopefully starting to rethink our species’ way of life with a systemic perspective.

BD: What are you working on now?

BB: We are working on how to use Venice as a metaphor for other places around issues like reinhabiting downtowns and climate change. Our city holds a strong symbolic power which we want to use to speak about Venice as well as the world, delocalising our work. We are producing alternative geography, civic and urban education workshops for kids. These workshops will come together after facilitating the exchange and sharing of the kids’ experience of the place where they live. Looking at the world map adopting a perspective that takes into consideration the common challenges faced by places very different, such as, for example, Venice, Jakarta and Miami, can be a powerful metaphor to show this “interconnectedness” that is at the base of our poetics.