Maggie Hazen is a New York-based artist born and raised in Fern, California and works between installation, video and performance. She holds an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design and has done collaborative research at CERN, MIT and Brown University. Through an empathetic approach, her work considers and critiques the representation of women within the structures of power encompassing our physical and digital worlds. Her solo exhibitions include Brown University’s Granoff Center (2016); and the los Angeles Museum of Tolerance (2012) for the 20th anniversary of the 1992 lA Riots. She was also featured in the 3rd International New Media Art Exhibition at the CICA Museum in South Korea and her past exhibits include OBO at Microscope Gallery, Brooklyn, NY (2016); and The Boston Young Contemporaries, Boston, MA (2014). She studied at the European Graduate Studies in Switzerland to research art and estrangement where she also exhibited her work. Her residencies have included I:O at the Helikon Art Center in Turkey (2017), Vermont Studio Center (2016) and a collaboration with Pasadena Side Street Projects (2014). Hazen teaches at Bard College in the department of studio arts and experimental humanities.

Performers: Maggie Hazen & Marisha Lozada Videographer: Eliza Doyle

2016

Lisa Andreani: Did you attend art school?

Maggie Hazen: In the spring of 2016 I graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) with an MFA in sculpture. Prior to graduate school I attended a small liberal arts school in los Angeles where I studied studio arts with a concentration in sculpture.

L.A.: What influenced you as an artist growing up?

M.H.: Growing up in Southern California, I was heavily influenced by Hollywood movie sets and hyperreal environments such as Disneyland and video games. As a young girl I spent considerable time backstage on the set of the ‘90’s sitcom Rosanne, my twin brothers were child actors on the show. I was always fascinated by the dichotomy of an on and off stage environment and was particularly fascinated by what the camera couldn’t see. I was interested in how the illusion was constructed. This is the same feeling I carry with me as I walk around lA. I wonder what identities people are performing and what is really happening “off stage” or out of sight. This is the same feeling I carry with me concerning identity as I walk through the streets of lA wondering what identities are being performed for the crowds and what is really happening off stage. The lA landscape is dotted with theme parks, strip malls, and entertainment complexes housing laser tag arenas, bowling alleys, and minigolf. Growing up, I would switch my perception to thinking of myself as an avatar in a land filled with homogeneous housing tracks and manicured lawns. I became a character in my own Sims world interpreting my experiences through an out-of-body lens, ultimately cultivating my own mythologies. RPG video game simulation influences how I choose to render these lands, much like Roller Coaster Tycoon or World of Warcraft, and lARPING groups, where individuals quests for power and control over territory adding to the lands history through new mythology. I was also influenced by my father who is a professor of philosophy and religion, I spent considerable time reading and pulling books from his towering bookshelf. Many deeper spiritual questions which influence my work come from my readings growing up.

L.A.: How did you get into art? Can you talk with us about what your approach is related to?

M.H.: I was making art at a young age but it wasn’t until high school where I began to focus my attention on pursuing fine art. I had two grandmothers who painted but not professionally. I remember my grandmother first introducing me to oil paints. I was a horrible painter! I made really bad abstract expressionist work, way too angsty. More than any formal training in art, I think what influenced me the most was singing karaoke to Avril lavigne, Pink and Madonna in my Jr. High bedroom in front of the full length mirror. I think I really wanted to be a pop star at the time. The fusion of my performer artist complex began to form at this stage in my life.

L.A.: Was the residency at Vermont Studio Center in 2016 a good experience? Describe this participation to us.

M.H.: I had a good time in Vermont. I made a handful of friends I am still in contact with. The program was set in a beautiful enviornment, I think its important to retreat into the woods for a time to make art, removed from your day-to-day life expectations and distractions. I spent a month just focusing on producing new work.

L.A.: Can you tell us in detail about your work? What is your goal?

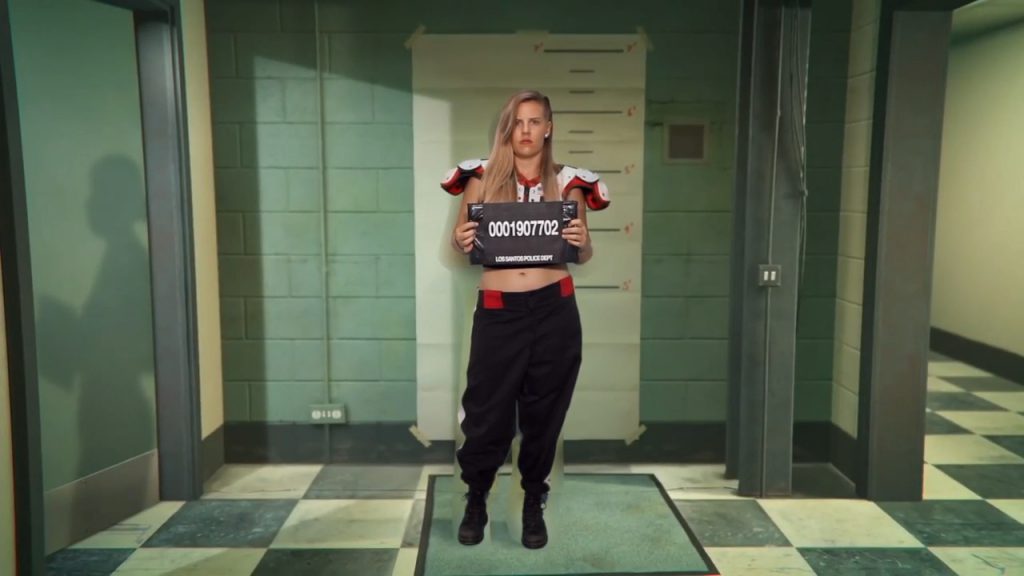

M.H.: In the work, the computer becomes a portal into infinite streams of information bridging the past, present and future morphing into metaphorical wormholes or a hypothetical stasis, distorting our perception of reality. With new technological advancements time is figuratively compressed. With just the flick of the finger I can surface ancient Sumerian texts like the “Epic of Gilgamesh” and one second later read about new technologies aimed at terraforming Mars. The strange objects I use in my sculptures form symbols, engaging a murky place between known and unknown physical realities “no places,” abstract digital universes and fantastical realism. I look into and explore the fabric of both our material reality, as evident in modern physics and cosmology, alongside notions of possible spiritual universes where myth, magic and legend combine. As a result I find cultural connections: bridging time as it relates to ancient history and science fiction. Secondly, I have been fixated on this notion of the impossible body and in its limitation and failure. I am not talking about the impossible body as far as industry standards are concerned: model standards, size 2, have to be six-feet and walk the runway. That’s not an impossible body, that’s a real body, though often photoshopped, although obviously a fashion standard. An impossible body is one, given our present technologies, that is literally unattainable, for instance, augmented bodies, technologically enhanced bodies, virtually transcendent bodies aimed at achieving mythological or fictional powers. Concerning this particular subject matter, I am interested in the human drive to find power through the manipulation of the body—focusing on how the future body or the screen body lures an audience by both fear and awe. Giving rise to the possibility of power driving the human machine. The result of this drive is something I would call the hyperbleed of human fantasies in popular culture via the video game industry, movie industry, and other fictions which market powers of escape, embodiment and a liberation from weakness. The hyperbleed is a term I have made up to describe the relationship between the images found in screen space which directly influence our physical bodies.

However, my dream is a version of the human that embraces the possibilities of information technologies without being seduced by fantasies of unlimited power and disembodied immortality, that recognizes and celebrates finitude as a condition of human being, and that understands human life is embedded in a material world of great complexity, one on which we depend for our continued survival.

L.A.: Can you describe the relation between your subject and your medium?

M.H.: My relationship to my subject and medium are directly linked to the influence of technology on the body. Seduced by cinematic spaces and ever-expanding screen culture, I can morph into Bowie, shave a beard, shoot lasers out of my eyes, pop like Britney and run through virtual los Angeles. This play, while still a fantasy, allows for a briefencounter with the liminality between futility and transcendence.

It also allows me to negotiate the combination of body, self, and space in order to investigate the estrangement of gender—seizing alienation as an impetus to generate new worlds. Using identity, it stresses how affinity comes as a result of otherness, difference, and through the perpetual process of becoming.

Merging reality and fiction, the work suggests a world coloured by desire. In a screen space, I can construct different versions of myself in a multitude of fragmented fields. I can fabricate a role and play it. I can shield myself and communicate as the other. I can compress, rip, render, filter, fade and splice myself. I can become invisible. I can build any setting for me to become anything but only a representation of that thing, perhaps only a slight likeness. As such, the image is — to use a phrase by Walter Benjamin — without expression. It doesn’t represent reality. It is a fragment of the real world. My work has moved into an exploration, confrontation and an embodiment of speculation within the framework of identity, technological bodies and image culture.

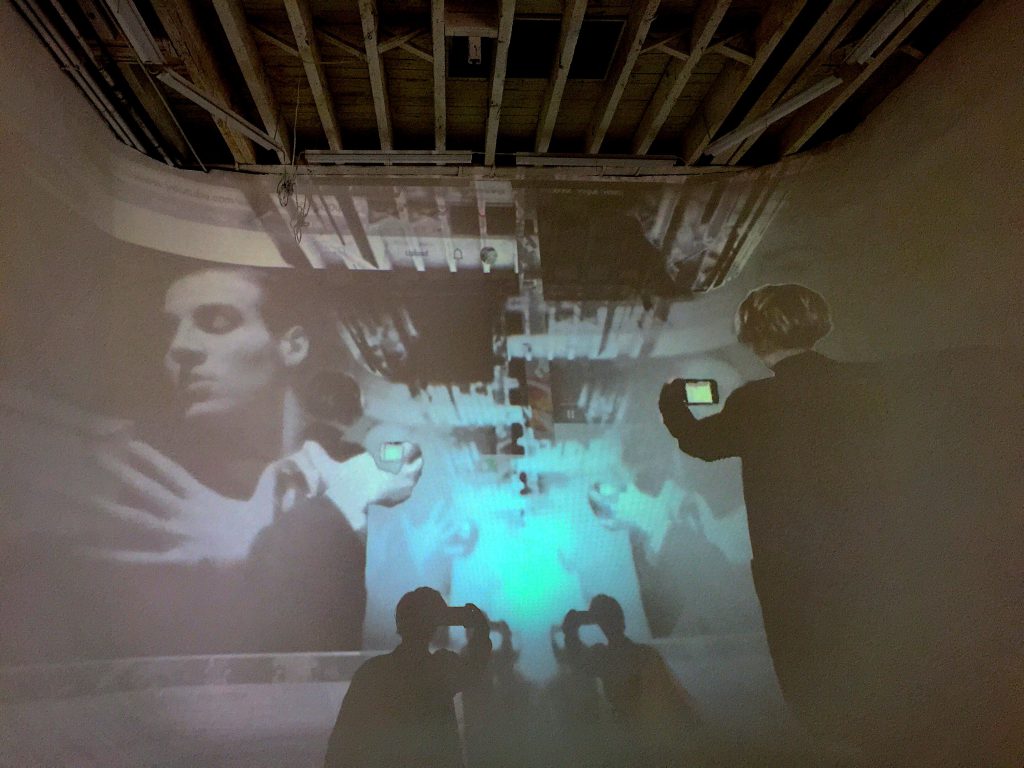

L.A.: What about the live video performance Everyonesaghost?

M.H.: Everyonesaghost was a project that explored the notion of “empathetic otherness.” I pre-produced a series of faces of YouTube personalities and inserted my face into theirs through a device I built which allowed me to insert myself into the video in real-time. This generated a glitch effect where my face never fully fit with their faces causing a distortion or mis-step. I wanted to visually depict a form of empathy and what it felt like to wear the mask of someone else. The performance was a deeply personal experience and I do think the impressions of becoming another has left a deep impact on me.

Anemone. Live Video Installation Rollgate Studios, New York 2016

L.A.: And what about the other live video performance No Man’s Sky?

M.H.: The digital performance No Man’s Sky was influenced by a series of questions I generated, questioning fantasies about transcendence. It was constructed to investigate the human desire to surpass the body. It questions what it means to be liberated from the self. I was interested in why humans construct fantasies promoted by curiosities such as the desire to fly or to become invisible. This desire could be rooted in playful escape but it also directly influences our reality. Just look at the worlds growing national military industrial complexes, thriving entertainment industries, and technological mega-empires.

L.A.: What is the work D-Lab inspired by?

M.H.: D-Lab stands for “Daedalus’ labyrinth”. In Greek mythology, the labyrinth was an elaborate structure designed and built by the legendary artificer Daedalus for King Minos of Crete at Knossos. Its function was to hold the Minotaur eventually killed by the hero Theseus. The work is partly influenced by the labyrinth and partly influenced by the mechanics of an orrery design. An orrery is a mechanical model of the solar system that illustrates or predicts the relative positions and motions of the planets and moons, usually according to the heliocentric model. At the time of its making I was influenced by the spiritual and contemplative nature of spiritual labyrinths where getting lost is part of the journey of discovery, typically causing the wandering body and mind to think about questions that cannot be answered.

For me, looking upwards and contemplating the fabric of space and time draw me closer to forms of power that are way bigger than me. I am both scared and exhilarated by that power.

L.A.: What are you working on now?

M.H.: I am currently working on a series of sculptures and videos called “Infinity Goddess.”This ongoing series of work features the triumphs and failures of iconic or mythological female figures in hyper-masculine cinematic spaces. Its likely this body of work will have no end.