“More than a career, I like to define mine an adventure”.

These are the opening words of a young Achille Bonito Oliva, Neapolitan intellectual, in the famous interview conducted by Vincenzo Sparagna and included, in tricolor colours, in issue 6 of the legendary magazine FRIGIDAIRE (Primo Carnera Editore).

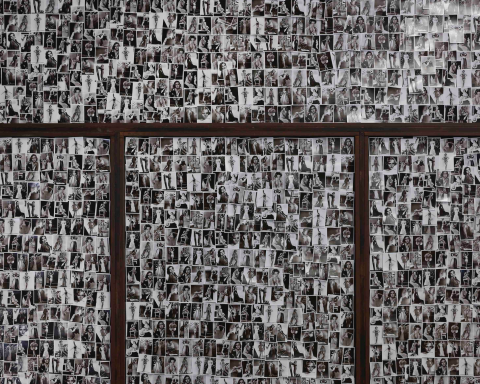

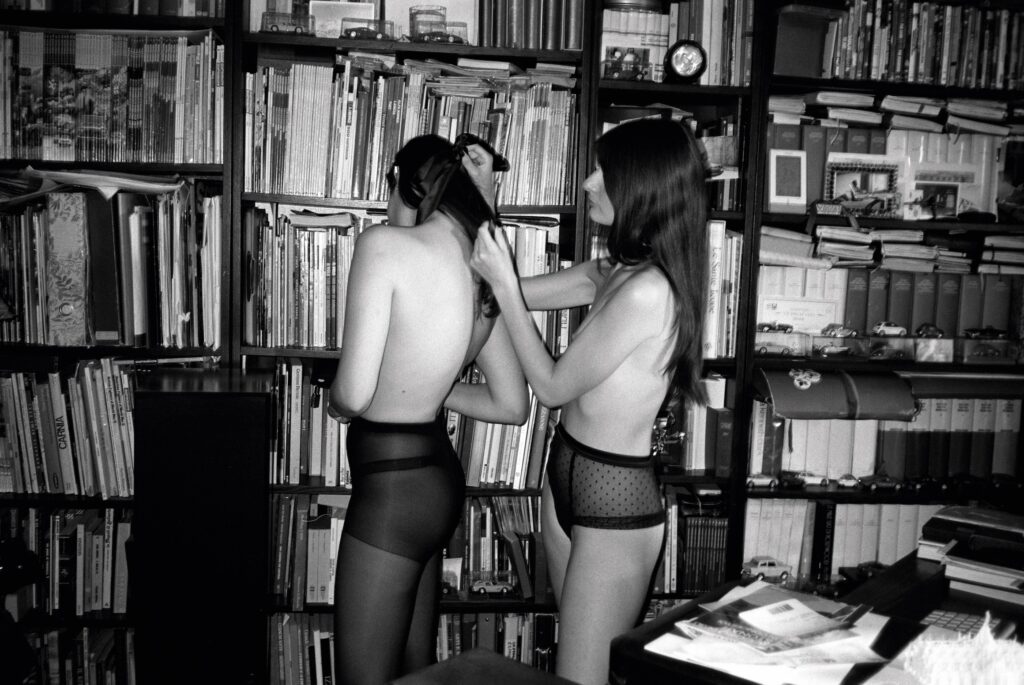

Now a cult object, the publication published on the 6th of April 1981 featured the reassuring wording on the cover: ARTISTIC NUDE. It was a real scandal, the Neapolitan critic appeared completely naked, lying on a wooden sofa covered with white upholstery with blue tomor motifs, elegant and confident, without filters. The shooting, created by Sandro Giustibelli, is still famous today, a sign of the personality of a cumbersome curator, who does not place himself and his role in the background compared to the artists and their works.

Just over forty years later, what has changed?

What is the role of the curator and what is his-her image in the current universe of contemporary art?

We talked about it with Manuela Nobile and Sara van Bussel, artistic director and curator of LOOK AT ME, a format of three exhibitions that reflects on the body, on the freedom of artistic expression and on the world of the night through experimentation and insertion of contemporary art in unconventional places.

We asked them to lay themselves bare, in every sense, to quote the father of citationism, to discover how curating today is a fundamental path, that is rich in skills and requires real coherence between actions and words.

Marco Roberto Marelli: Manuela, can you tell us who Sara is?

Manuela Nobile: To grasp the essence of the person Sara is for me, it is sufficient to associate her with the moment I met her. A bike tied to a pole, an old cafe, even a little run down, and a glass (or more) of wine. Sara: “Would you like to organize an exhibition in a strip club with me?”. Me: “Give me pen and paper so we can sign this marriage right away!”.

I don’t know much about her past, but I’m happy to be part of her present because Sara is a great source of inspiration for me, needing to be continually stimulated as I am. She is not afraid to get involved and in every conversation or message we find topics or themes for possible new projects that could go on forever. Sara is an altruistic, sincere, true, transparent, determined, ambitious and independent person. These are some of the aspects that I also find in her writings s and in the way she communicates, with few frills and a lot of substance. Let’s be clear, in Milan you don’t make a living just by making art. Even Achille Bonito Oliva couldn’t do it, let alone us! The fact that she is busy all day like me makes our synergistic work almost like an outlet.

She is certainly more precise, which is why she constantly reminds me of the week’s appointments or the calls we have set to prevent me from forgetting them, like a continuous reminder. If I have to tell you in detail, Sara was born in Salò, but her surname may suggest Dutch origins, the country where she lived for several years, precisely in Amsterdam. Today she works as an art advisor for a historic design gallery in Milan and is head of research for the OTTN Projects collective, with which we organized the first LOOK AT ME.

The visionary Giorgia Ori, the founder, put us in touch. Thanks to her I found myself with a colleague, but above all a trusted friend, who could now blackmail me because she knows everything about me, we literally exposed ourselves.

I hope this companionship stays beyond this professional project and that our journey together never ends.

M.R.M.: Sara, Manuela said that you are a trusted friend, beyond the working relationship.

Sara Van Bussel: Manuela is a colleague and sister. First of all, I believe that Manuela is an incredibly talented Art Director. Her artistic direction touches on multiple aspects: from aesthetic research, in continuous study and evolution, to extremely complex graphic and technical skills up to the generic directional management of communication, which translates into sensitivity to content, attention and care to the smallest details. The thing I really like about Manuela is that she always puts herself to the test, she always raises the bar, pushing herself with admirable strength, not out of competition, as it is for many, but out of her personal growth and desire, which makes her work even more valuable. In addition to esteeming her infinitely for her specific professional skills, Manuela is a strong and capable person who navigates work environments well and knows how to manage complex situations. Her general attitude towards things is of problem solving, she is able to control and ponder any difficulty in the work process without panicking, often supporting me emotionally. In addition to sharing a precise ethic and a vision of the status of art, when making artistic projects I also believe the emotional component is fundamental: together we create projects that talk about life, that talk about complex personal themes, and even though they are work to all intents and purposes our project cannot ignore a visceral affinity. It is important to say that with Manuela I feel safe, and I believe this is essential in order to do what we do.

M.R.M.: Manuela, do you think that your “couple practice” requires a real centralization of roles or is the creation of an exhibition nowadays a collective event, where the term curator explodes, opening up to different collaborations and skills?

M.N.: I will respond by quoting the words of Achille Bonito Oliva himself: “the problem is that when we talk about art we must talk about an art system. The work of art does not exist in itself. It lives on a system of relationships: work, public, criticism, market and museum […] If there is no publisher who publishes you, your identity as a writer does not socially exist […] no one accused Moravia of to be a sellout in the culture industry.”

Every person involved in our exhibitions is of vital importance for the success of the project. Taking care of every aspect, we consider every person who helps us with the setup or who gives us an opinion on how to use the lights as part of the team. I’ll give you an example.

A few seconds before Michele Rizzo’s performance in the strip club we had to activate various mechanisms, lighting the smoke machine, turning off all the lights, including those in the bar, and start the music.

All systems designed and architected on site thanks to the support of the technicians present. Speaking in more detail about the two of us, as I said before, I met Sara because she and OTTN Projects were looking for an art director to take care of the communication of the exhibition. I would have to find sponsors, media partners, take care of the press review, the coverage and create the graphics. However, I believe that Giorgia also wanted to involve me because she knew me as the curator of State Of, an artistic project founded by me in 2019. This also meant giving a more sensitive and familiar contribution to the type of work they were proposing to me. This is to say that neither of us has ever dealt with just one thing and I believe that the further we go, the more this will be the case. Sara’s theoretical skills in writing, in the mastery of the fifty thousand languages she speaks or in the selection of artists are certainly more effective than mine, which are undoubtedly focused on the use of programs for the creation of graphics or on the aesthetic eye for the care of communication.

So yes, I believe that the creation of an exhibition is now a collective event. Or perhaps we were just lucky to have found ourselves collaborating so spontaneously and listening to the voices of others without any narcissism.

M.R.M.: Sara, do you believe you really are that open to dialogue?

S.V.B: Manuela said it all, I absolutely believe that every single person we involve is essential to the realization of each project. Everyone brings something, and the specific qualities of the people involved is what makes each exhibition unique. Regarding Manuela’s work and mine, we certainly have areas that we deal with individually – as Manuela said, I always write the texts and Manuela always takes care of the graphics – but all the other choices are always shared and certainly the result of dialogue.

M.R.M.: And how do you enter into dialogue with artists? How do you “construct” exhibitions with them?

S.V.B.: The selection of artists occurs organically depending on the project. It happens that a conceptual program inspired by the location is first shaped, and then the artists are chosen, as well as the opposite: a specific work leads to curatorial reasoning that we find stimulating and which subsequently leads to the construction of a project. The approach to the artist is always, in reality, conveyed by his work, it is the practice that remains central, and to which we want to give space.

For me, curation remains above all research, which means that both before contacting an artist as well as during the working process, my-our role is one of constant study, theoretical and otherwise. There would be a lot to say about the work-artist distinction, at the moment I will simply underline the fact that we always approach artists on the basis of their specific work, on which we can then build. First of all, we always ask the selected artists if they also see an affinity with our project, from there we proceed to decide whether to exhibit something that already exists or whether to create something together. These choices are unfortunately also dictated by practical issues such as timing and budget, but our modus operandi certainly leaves a lot of freedom to the artist to propose, create and even involve third parties. It is important for us to follow the creative process and have free and solid communication with the artists, it is the only way to achieve the full realization of an exhibition and ensure that the project is felt by everyone. As regards to the type of artists we choose, I reiterate that I usually focus more on the work itself than on the artist, certainly preferring artists who already have an established artistic background, this not for discrimination but for accessibility to research. Achille Bonito Oliva said “We are looking for new artists because we still want to experience a small emotion, to see the Madonna”. I believe that more than new artists we are looking for new angles from which to observe.

M.R.M.: Your “preferred corner” can be identified in the research on the body: how do you investigate this indivisible dichotomy of internal and external, private and public?

SVB: I see our curatorial practice as asking questions. An artistic work is never an answer, it is the concretization of a research, the materialization of an inquiry. What we try to do with our projects is exactly this, give space to different artistic forms that question the concept of the body and investigate its role and its entity through a creative formal elaboration.

Internal and external, private and public are just some of the dichotomies analyzed in recent exhibitions: when we talk about the body we talk about anatomy, sexuality, pleasure, and therefore also about property, work, individual and collective identity. Our attempt is to dissect the concept of the body and place it before a myriad of different perspectives, avoiding univocal projections that lead to a trivialization of complexity. The key, in our opinion, lies in the stratification, in the rhizomatic nature of the question which translates into art in a true way because it is free, without pretensions to limited answers but with a critical sense, matured by the awareness of the risk and the full acceptance of the experiment. The work, whatever it is, is always true precisely for this reason, because it is an attempt, it is put into play, it is courage. Asking and above all asking ourselves questions, as a person, as a physical and ideological body, as a society, is an act of courage, and should be celebrated.

M.R.M.: What questions does the “LOOK AT ME” trilogy raise?

SVB: This trilogy represents mine and Manuela’s attempt to bring contemporary art to places in life where the cult of the body is central, accessible, and above all not limited to a pre-established social class, hence also the choice of the night (on democracy of the world of the night there are several interesting articles, I recommend The Promise of the Night by Lieke Knijnenburg). LOOK AT ME was born from the need to talk about the body in a new way, in new worlds: there is a need to talk about pleasure, property, identity, there is a need to ask questions, there is a need to share them together.

The title, LOOK AT ME, is also inspired by this: it is a simple request, look at me, I am here and I need you to recognize me, ‘’without difficult words’’, quoting Achille Bonito Oliva once again.

The fact that in the Italy of 2023 Manuela and I lay ourselves bare, even de facto through the photographic lens, but we cannot expose ourselves in the same poses assumed by a male curator in 1984 without risking losing our jobs or being frowned upon, it is absolute demonstration of this urgent need.

M.R.M.: How did this path – that generates an archipelago where life and art overcome the poverty dichotomy and pose the dilemma of reality – arise and evolve?

SVB: The project was originally born from the desire of OTTN Projects to explore the body in the post-pandemic, a desire that was then shaped in the choice of the topical area of the strip club, dedicated to the cult of the body and king in the world of Night. The making of LOOK AT ME 1 was an extremely complex project; Since I was alone in Milan, I asked the founder of OTTN Projects, Giorgia Ori, if she knew anyone here who could help me. This is how I met Manuela, and from that moment on the project became ours in all respects.

The first edition was a big step, a leap into the void for the two of us as well as for all the artists and partners involved: we worked for almost a year, learned about the place and its workers, we understood how to navigate that world and how to stay inside it, to be able to approach it in the right way and integrate the work of the various artists into that environment so rich in meanings and symbols. The success of LOOK AT ME 1 was our strongest feedback: we understood that what we were doing was important, that there was a need for this type of approach to contemporary art and that there was still room to work.

Hence the choice to create a trilogy that followed the same research thread as LOOK AT ME 1 but which each time touched upon a different aspect of the same theme: the body. In addition to bringing attention to a subject that is increasingly relevant to us (we also think of bodies as migrant bodies, or as subjects of diseases, in short as intrinsic containers of what actually happens in the world today) it was also important for us to go and explore another ways of making art. Starting from the assumption that the approach we want to use to talk about this topic is an artistic one, our will is rooted in wanting to create culture. And creating culture means entering into things, into everyday life, into the places where it takes place. It makes no sense for us to go and explore this theme in pre-established institutional centres, as these are in themselves already aimed at welcoming a sector audience, and also adhere to the rules that this cultural capitalism provides.

M.R.M.: You spoke of “democracy of the night world”; what universe do you want to describe?

SVB: We chose the world of the night because that is the place of possibility. In the Groene Amsterdammer I had read an article some time ago by Ewald Engelen, who describes the world of the night as ‘’A temporary anesthesia of neurotic pain caused by the neoliberal struggle of all against all’’.

Addressing the theme of the body, questioning it as a physical, ideological, private and public entity, I asked myself what is the place where different bodies mix, where everyone can access, and I thought about the night, asking myself if I shared this opinion.

I found myself thinking about the origins of nightlife as we know it: from the history of ethnic segregation suffered by African Americans for centuries – which led in the early Seventies to the creation of the disco or techno scene through figures such as Kevin Saunderson or Frankie Knuckles, who in that context gave birth to new musical forms because they felt recognized, safe, in the night – up to the present day and the birth, for example, of the German organization Reclaim Club Culture, which responds with the organization of raves or night parties at the political positions of the Alternative für Deutschland. It is enough to carefully analyze the history of the night to understand that, unlike what Engelen claims, the world of clubs, where we dance, sweat, experiment, is par excellence the place of meeting, of possibilities, of exchange and solidarity; and of resistance. The sociologist and artist Bogomir Doringer, for his doctoral research ‘’I Dance Alone’’, analyzed the world of clubs, studying the movements and non-verbal forms of dialogue of the public through the positioning of cameras, addressing club culture as a social political phenomenon to all effects. Where Engelen talks about anesthetization, I instead say that the night is, on the contrary, precisely an awareness. Going to investigate with critical capacity the concept of the body as Manuela and I understand it requires that “place”, because it is a temporal space where who you are, what you do, where you come from during the day does not matter, you are a self-conscious identity, and that’s enough. This is the world of the night that we want to tell, where, to quote Marian Donner in her Book on Self-Destruction: ‘’he who dances is free’’.

M.R.M.: Manuela, within this world, are there any limits that have to be placed on the freedom of artistic expression?

M.N.: No, there are no limits in my opinion, on the contrary, they should be abolished if there were. I am probably conditioned by the precise angle of this interview, but I would say that the most important barriers to break down are modesty and prejudice.

Perhaps only at the time of the exhibitions in the Parisian Salons did anyone who looked at a painting have the illusion that nothing existed outside the established and framed limit.

I believe that the artists that Sara and I are looking for are all open and intelligent enough to find, even in potential limitations, such as the complexity of an unusual exhibition space, the strength to create site-specific works or a new interpretation of previous works. If anything, trying to place limits on creative freedom means giving an artist the opportunity to rebel and the result is even more satisfying.

As a normal factor in history, when living conditions change, methods and needs also change. Art has always been “shown”, but over time the intentionality of its being shown has radically changed.

We have gone from a question of prestige and privilege for a few to the desire of accessibility and the wish to reach everyone. With the exhibitions we are carrying out, the idea is precisely to mix multiple audiences and eradicate these aforementioned limits.

Today, even in the world of art, hybridizations of forms are opening up. Creativity and intuition, fundamental qualities for an artist according to the idealistic and romantic tradition, find new stimuli in daily life to continuously reinvent themselves.

M.R.M.: So, you don’t set limits in your curatorial activity? How personally and intimately involved are you in the events you create?

M.N.: The only way it’s possible for us to make art coherently is to recognize and dissect our way of life.

Invading spaces with a strong identity or that we deem politically and socially interesting, and not remaining stuck within four white walls, allows us to have a kaleidoscope view of the world. This method is simply the mirror of our habits, neither of us could ever act differently, curious as we are.

Today I believe that living the night, studying the relationships and reactions of the people we meet along the way, can be compelling because it opens the doors to moments of continuous reflection and exchange.

We do not exclude that something else could stimulate us tomorrow, paradoxically even the opposite. The coherence in the projects lies entirely in the selection of the artists, as Sara has already said, which is certainly a consequence of the choice of a place or vice versa. We have no pretense of claiming our role as curators to bully others, if we choose an artist we must find the most suitable place to do justice to his/her work.

Everything must be harmonious and we must all work synergistically in the same way so that quality work comes out, we must live in the same spaces and speak the same language for some time.

M.R.M.: Even for this interview the “place” is fundamental. In the 1980s, the physically exposed role of the curator caused a scandal, today it would probably go unnoticed. In this re-interview, what is the point of proposing your nude shoot, what message do you want to convey?

M.N.: In both of our exhibitions we touched upon the theme of the body and the freedom of artistic expression, also taking on possible responsibilities linked to the world of strip clubs or clubbing associated with a certain potentially complex and restricted circuit ,that hardly intersects with visual art or does so unconsciously. So the proposal to recreate this interview is in fact perhaps very non-random. Talking about art by taking on, embodying the role or simply underlining the fact of being two women is not a topic I prefer. In this particular case, however, we feel the need to emphasize our position. The images of a career man, successful and certainly of a more mature age than ours, however much they may have caused a sensation, will never be as strong or superficially misunderstandable as those of two young curators. If, as said before, we like to take risks, perhaps we have outdone ourselves with this.

Ours is a courageous stance on exposing ourselves and not being afraid of being pushed into a definition, which is why we are still undecided whether to give ourselves a name as a creative duo or not.

See our shooting as a parody or as food for thought, criticism or whatever you see in the interview with ABO.