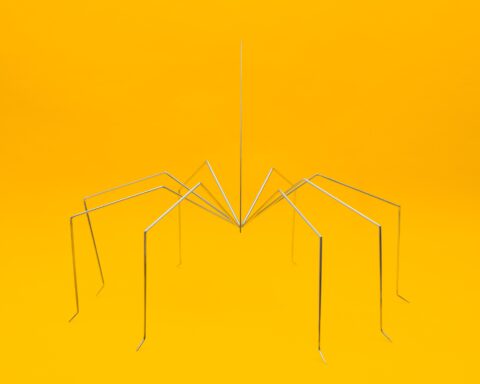

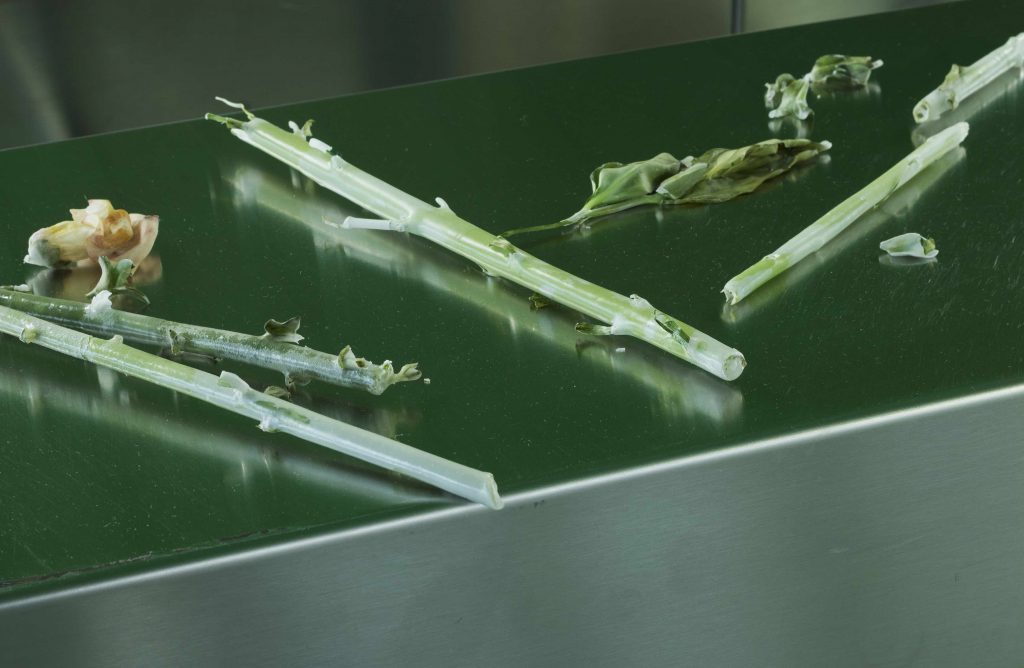

Andrea Barbagallo (b. Roma, 1994) creates biodegradables artworks, positioning between Art, Nature and Technologies. Each work is produced by technological tools, like a 3D printer, and, once created, it becomes an anthropomorphic being who generates symbiotic connections with space. Thanks to the study of materials and shapes, Barbagallo’s artworks give born to narrations about worlds and bodies, essential themes for the artist.

Installation view at Dimora Artica, Milan Photograph Andrea Lacarpia. Courtesy Dimora Artica and the artist

Gianluca Gramolazzi: You studied Painting at the Academy of Fine Art of Brera, but your works have just something to do with this medium. When and why did you start to create sculptures? Do you think there is a boundary between the different mediums?

Andrea Barbagallo: Starting from the idea of rethinking a type of living and autonomous art, the world of sculpture seemed to me the most suitable to restore the vital force that the work requires. For me, creating three-dimensional objects with vital power means returning them to a world that is traveling towards a continuous metamorphosis. Over time I have tried to expand my concept of embodiment on other mediums, also reaching painting. With painting, I realized that it was possible to animate images by making them screens, just as I could transform into bodies inanimate objects. The fusion and the exploration of the different media are necessary to create a life where it seems not to be present.

GG: Your early projects, as the Kipple Project, are conceived to be related to Nature. Nothing new, if we think about the history of art. Why do you think it is important to have a dialogue with Nature today?

AB: My work intends to take up the aims and objectives of Arte Povera and the most recent Bioart to lead the work towards the exploration of the body and the vital in order to free it from the power of man. When I think of nature, I imagine a world without men but with their instruments, which live and multiply without ceasing. Creating autonomous works means showing possible and future visions of a world destroyed by the desire that man has to manipulate life. The works can thus become the memory of their creators, capsules of the time of the man who was and perhaps will no longer exist. If the work merges with nature, in my opinion, I guarantee eternal survival, in other forms, in many places.

GG: The natural element is integrated with technologies. Why do you create this counterpoint? Is it related to posthumanism?

AB: When we talk about technology we always talk about men. Men who create machines and men who use tools. Today, these tools are able to do things without our presence, even our opinion. A shocking thing if we think that everything should concern us. Thanks to the new machines that build other machines, my hand only serves to create the starting input from which the work will be created, so that my body remains an intruder to the project of the work. Nature and technology, in my research, hold hands to live symbolically towards their liberation from man. Posthumanism enters when the rotary axis does not focus on the human body, but on the presence of other life forms, capable of taking over the reins of the world.

GG: One of the points of your practice is the questioning on the immortality of art, but also of the body. Could you tell something more about this?

AB: As a substitute for meat, the concept of body is closely linked to the essence of my work. I consider my works as surrogates of a physicality linked to man and his earthly presence. Stimulated by the vitality of other living beings, the works become bodies, which feed on the “bios” and change over time. The question of immortality simply derives from a connection to the second law of thermodynamics, or to the circle of life described in the Lion King, as the body’s inability to disappear and completely disperse its energy. The work changes constantly, penetrating more and more into the natural cycle that deforms it and appropriates it.

GG: Some of your works are made of PLA, so, they will be modified by time, until disappearing. Do you think that it could be harder to sell your artworks to museums and collectors? And if so, how do you relate to the conservation of your sculptures?

AB: The problem about the conservation of the work and its duration is a question that unites all art and its history. As a changeable object, my works are often unpredictable and are subject to change if the storage conditions permit. The materials I use are often biodegradable and therefore decomposable. However, their duration can be increased or decreased depending on the environment in which the work lies. This attitude allows it to adapt to the place of residence and to become a procedural device capable of implementing autonomous mutations and freeing itself further from the possessive dynamics of collecting. However, I do not forget that my work lives within a system made up of objects and possessions. To allow the object itself to live independently and be a good investment for the market of the things that remain, the project will be unique and the only salable work, reproducible by the collector every time the previous one disappears, decomposing. My work is therefore divided into two: the first part is made up of projects, like potential forges from which the works come out, and the second of bodies, free from the grip of the market and the laws on the eternity of the artifact.

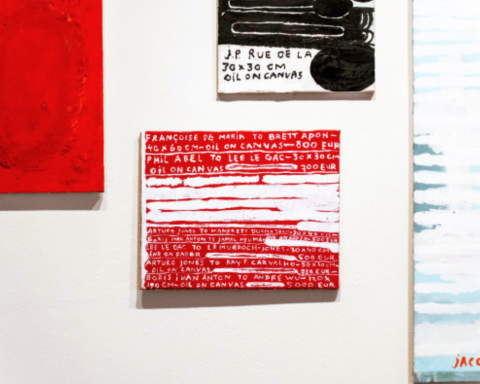

GG: Each exhibition is associated with a text where you immerse the spectator in the theme you are focusing on. But, in the end, texts are a reflection of the contemporary age, aren’t they? Could you tell me something more about your written production?

AB: To allow the work of art to become a witness of an endangered cultural past, we needed a voice, a find that served as a manifesto to express the concepts put forward by the works and the exhibition. Vacuum Confession is nothing but the random voice of the machine, which from a mere executor becomes the writer of situations relating to man but apparently confused and cryptic. If the work is a body, in my opinion, it must necessarily have a voice and communicate, directly and indirectly with the person who perhaps will come into contact with it.

GG: In the last 2 years, the evolution of your artworks speeded up. But now, which evolution could your production have? Are you creating something new?

AB: My work focused on understanding and creating bodies. A long work devoted to the exploration of life through machines and how to give them autonomy. Having understood these dynamics I decided to go further, automating the work and building displays capable of providing the works of environments and situations where they can remain alive. Nature is not the only place assigned to my work: if there is a place where the work dwells, it must have its own ecosystem. The display and the setting are therefore the second phase of my new job.

Curated by Rachele De Franco. Photograph Alessandra Draghi