The paintings displayed in this exhibition rely on a deeply human theme. Here, inside the walls of a building conceived since its foundation as the ‘Painters’ House’, two artists showcase the product of a residency held from February to April. Their reflection has archaic and obscure roots in the rock drawings, in the inescapable human desire of subjectivizing through Painting: that Ancient Foreigner, who since the dawn of time fascinates and bewitches, without ever conceding. Speaking the language of this foreign goddess, mutable and capricious, remains mostly impossible. Yet, she finds a way to reveal herself to those who unceasingly and completely try to chase her.

Lara Braconi and Piermario Dorigatti are similar in their attitude: they fully live through painting, showing the serene levity of those who have already accepted their destiny, and the troubled devotion that this sacrifice requires. Their life turn into paintings and their paintings bear the – sometimes unbearable – marks of life. Piermario has a frowning, authoritative air, almost intimidating at first, certainly defiant: but Painting is an elusive lover that makes him suffer while she lights up his eyes; for him sharing about her is not that easy. Lara is serene, young, and when she talks, she smiles with a deep respect; emotions flow over her face as the colours on her canvases. Both are painters in a totalizing declination, so vital, archaic and passionate, but rare.

Experiencing the time at the atelier of Casa degli Artisti, brightened, as many before them, by that intense light, united both by passion and by a peculiar friendship, their poetics have grown closer and the outcomes have been unpredictable.

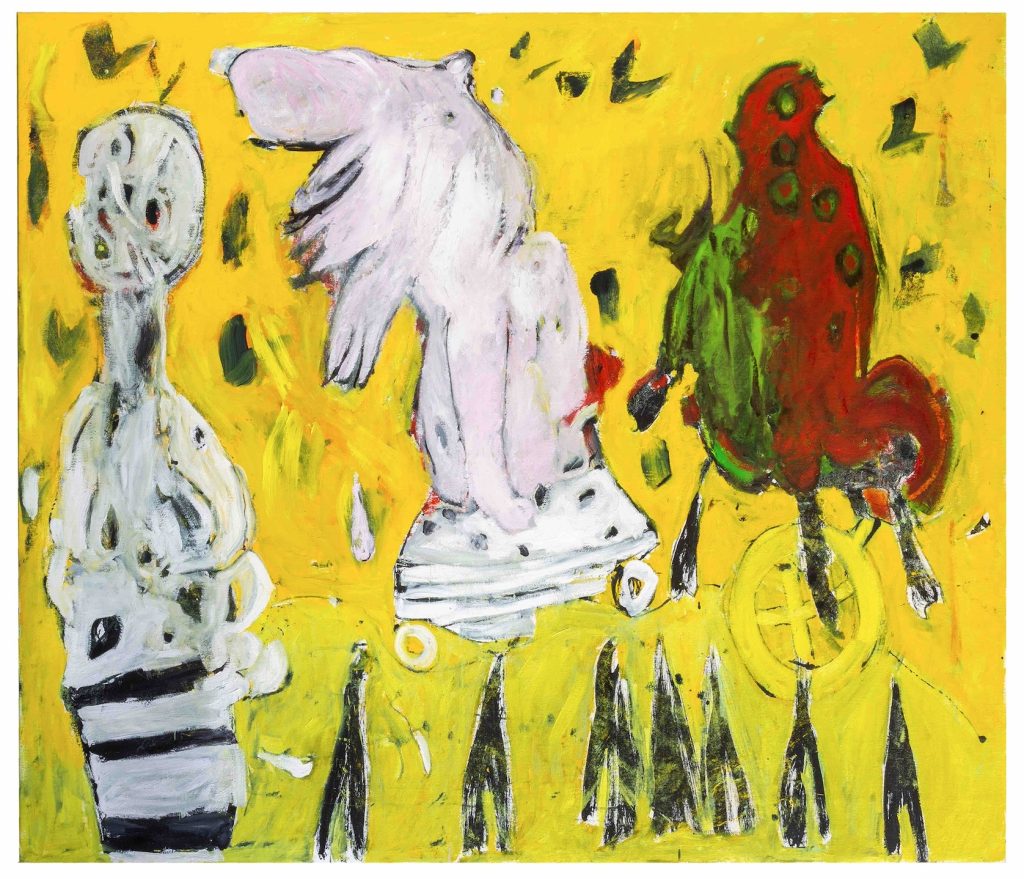

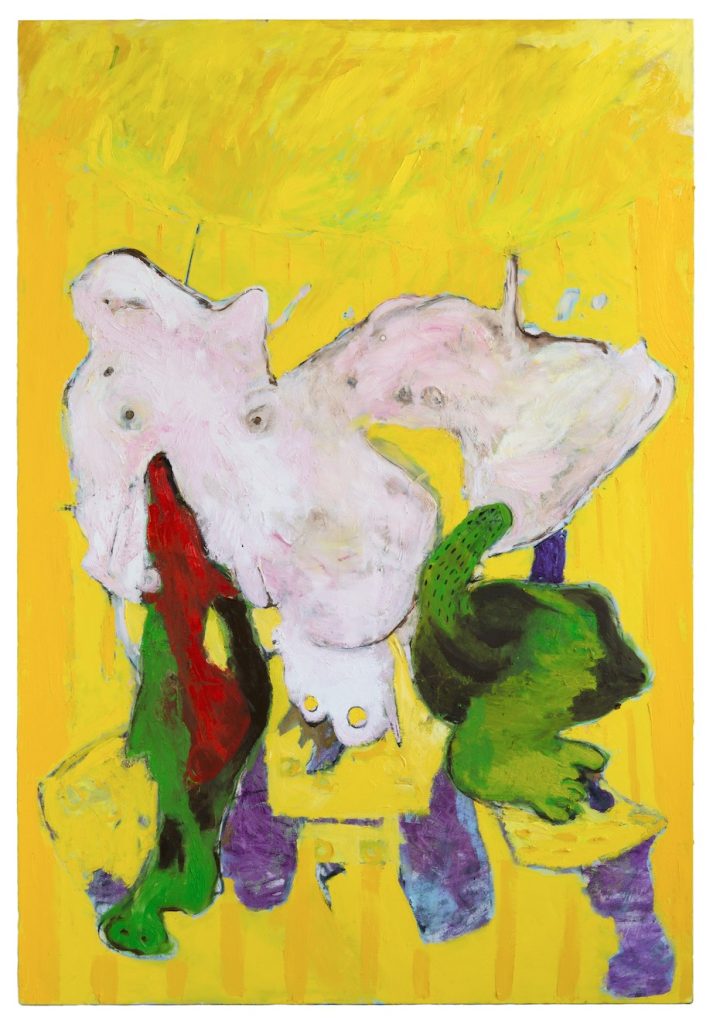

Dorigatti began straight off to set the seven canvases, in the grip of the automatic drawing: illuminated by that powerful light, the canvases seemed small to him. So fascinating, in the early stages of each, there were drawings in brushstrokes, figures, interiors pervaded by certain arabesque background that brought back to the chambres of a mature Matisse. Then, a slow metamorphosis in the process of painting: the transformation of the drawings through colours; thus, their persistent memory, which while transfiguring the images, appeared as an exfoliated membrane, almost a luminous residue. This reminds me of Piermario’s fondness for the myth of Dionysus, the jolly, sardonic god reborn from laceration. Hence, the demiurge-painter reshapes a pictorial matter, leaving it rarefied and dreamlike, inhabited by a limb of monsters we are not given to know. The “monstrous” is for him a liminal space, a constant nemesis that boasts two souls.

On the one hand, a grotesque bestiary of anthropomorphic and unexpected creatures appears on yellow backgrounds, where graffiti become ornaments. Constant presences are certain cephalic structures endowed with limbs, Lüpertzian distortions on the canvas, which even though they recall the medieval crickets present in Hieronymus Bosch’s infernal representations – In Amore Puro dramatically deformed in its Baconian tones, defintetly more ironic in Il Dubbio – and again in Lasciatemi il Sogno, where an almost scaly appendage ends in a paw of goat’s physiognomy. Imagery rooted in the South Tyrolean folklore, where the concept of ‘Hell’ is accompanied by the Krampus processions for St. Nikolaus. Seductive is the rosy glow of flesh, that becomes shapeless organic matter and doesn’t get lost in the two-dimensionality of the canvas. Yellow is still a preferential colour that enriches each work with strength, surely a source of security for the artist, who adopted it almost by provocation.

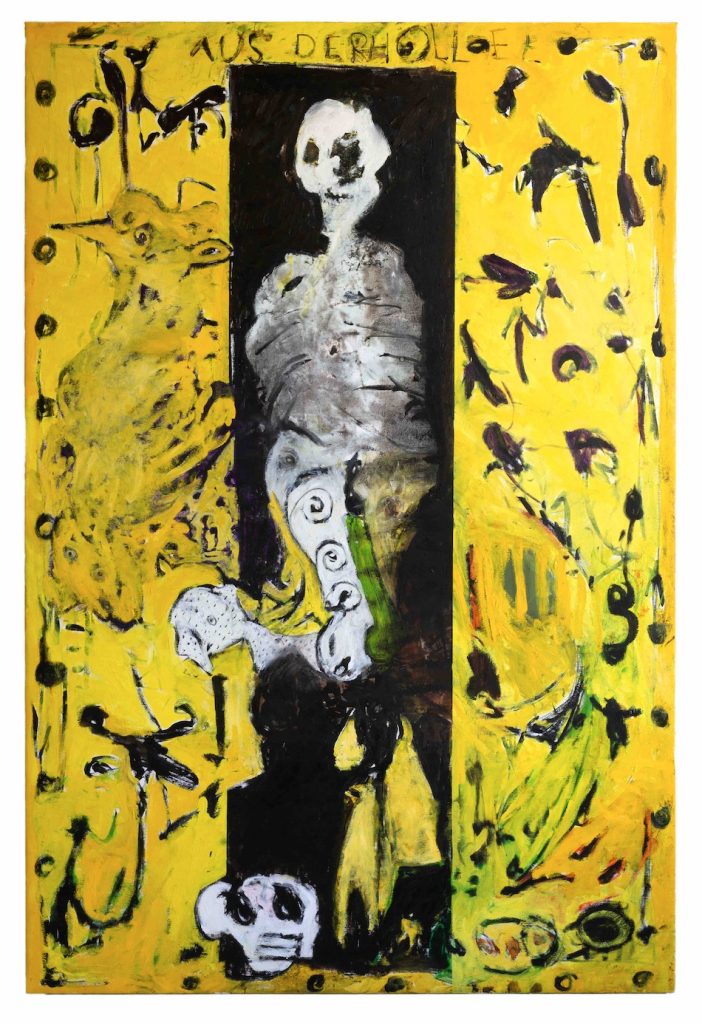

And then there is the darker, tragic soul, Aus der Hölle: a skeletal spectre emerges from a black abyss with a smoky torso, a disfigured skull, and only the lower part – the ileum and pelvic bone– are sketched with primitive details: dots and small curls. There are theatrical sceneries that gather the figure, while to the right, barely visible, remains the memory of something zoomorphic, perhaps a phoenix, a denied possibility of rebirth. On the ground, as in ancient crucifixions, a skull. It is evident the iconographic reference to the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, as well as the presence of the written word that becomes a signifier; a strong Pop component is also persistent, certainly actualized, as well as traces of the cartoon universe – I refer, for example, to Lasciatemi il Sogno – which hints at the narrative of the cartoonist Benito Jacovitti. Yet, even the most unbelievable beings accorded to their own titles are covered by an enigmatic beauty and by a very human lyricism.

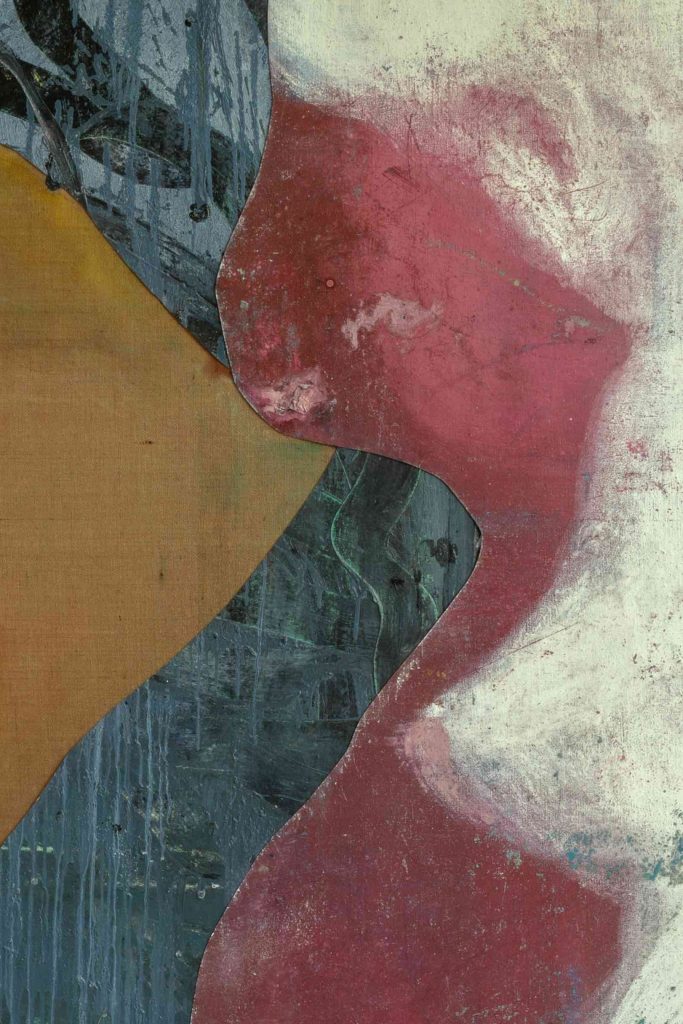

Braconi, on the other hand, welcomed the residency’s purpose by courageously devoting her canvases to a vigorous experimentation. I remember her drawing: she sketched forms in charcoal at first, like someone who seeks something pure that lingers to give itself, intent on refining its own mark, trying and trying again. And those primal, stenographic forms born on paper in more than three hundred drawings, suddenly dictated a direction to her. The canvases that began to appear in her distinctive process of layering, broke free. Leaving the overabundance behind, the possibilities multiplied. The stroke became more instinctual, more informal and immediate, almost street-like in certain brushstrokes. Then, the change: the canvases stripped, the image was led to resurfacing at the back, where it was just a residual, a leftover. Other canvases instead were cut, broken down and recombined on new canvases of cotton and raw jute, ingredients for the creation of new worlds. She gave the paintings a possibilities of figuration beyond themselves, almost paintings-objects in the end, composed of precious fragments, where voids and solids-memories of other lives, rhythm themselves in new harmonies. That is an opposition played between the colours’ strengths and the forms’ synthesis, a focus on the cadences of Joan Miró, deployed between the wide breaths and the essential energy of the figures.

It remains, inescapable, the creative power of the gesture, which combines the fragments of images. The colour, which previously had a structural role within Lara’s artistic making, becomes a plastic, combinatory opportunity and finds in this practice a new minimalism of figuration.

Thus, Esodo testifies a memory, a previous journey, of which just a title and the artist’s signature remain; Femmina instead is impulsive, unique, even in the familiar gentleness of some forms; in Coste Apuane everything is left to the eurythmy of colour, which wins over the rough jute, almost capable of rekindling in the observer lost memories and scents, perhaps never really existed. Lady Gradiva also follows this principle, joyous and sculptural twirls in glittering gowns, a nymph of inexplicable colour variations. Last, there is Cassa Armonica, where the four rib-shaped magnetic void has a totemic, figurative power: an echo of archaic music from the dark surface, as entering in a cave.

Lara and Piermario certainly are two very different persons: for generation, style, age, masters, and above all for character. Still, their poetics touch each other, speaking without any need for words. They give meaning to small things, to the time that passes and remains soaked into the canvases: a time made of hours, of faces, of encounters. Thus, each work is a tale of their everyday memories, a trace of their ephemeral, impressive moments.