A great public art project that can take up and update the PWPA model (Public Works of Art Project) established by the President of the United States Franklin D. Roosevelt in the thirties. This is the perspective proposed by Hans-Ulrich Obrist – Swiss curator and artistic co-director of the prestigious Serpentine Gallery in London – to overcome the difficult moment of global health and economic crisis.

Born in Zurich in 1968, Obrist spent his childhood away from the revolutionary turmoil of those years, in Weinfelden, a small town in the Canton of Thurgau, located about twenty kilometers from Lake Constance.

Referring to the self-narration proposed in a recent and long interview granted to the philosopher and artist Eugénie Paultre, three “periods” initially followed one another in his life: that of walkings, that of night trains and that of his first exile in Paris, city where he went with an old Volvo after winning a grant from the Cartier Foundation in 1991. All these phases merge and originate in an event from his early childhood when, due to a serious car accident, he was hospitalized. It was at that moment that his urgency, his mental frenzy and his physical inability to stay still were born. Many years later, through a brilliant and ironic description, the famous architect and his friend Rem Koolhaas reunited the youthful galaxy Obrist by writing: “It is said that he left his country of origin because he spoke too fast for the Swiss”.

This brilliant frenzy is the trademark of a curatorial and authorial process that has produced many epigones and a wide range of formats, tests and critical successes that are the symbol of a new way of proposing and spreading art: liquid, fast on the surface, universal and, perhaps, not completely horizontal.

The proposal of a great plan to get out of the profound economic and cultural crisis that has strongly affected the art world is only the latest act of a long journey that has profoundly influenced the epochal passage from the art critic, trained in prestigious universities, to the hybrid and elusive figure of the curator, a profession of which, for better or for worse, Obrist has become the prime example.

Self-taught by his admission, in his interviews and in his writings the concept of mentor frequently returns, the idea that in life it is important to find a guide, a person with whom to venture into the world. After the walks inside and outside of himself, the overwhelming need to travel to get to know, to dialogue with the artists arrived. We can start this epic story at the first meeting with Fischili and Weiss, which took place one afternoon when a young Obrist was free from school commitments. Thanks to a powerful memory he remembers everything about that day, in an epiphanic way he tells of how the two Swiss artists were working on one of their most famous creations, Der Lauf der Dinge, a work in which, cascading, a small event generates a subsequent one setting in motion the re-enactment of the history of the world itself, representing the intertwined accidental dynamics of life. From these and other meetings the idea was born of creating a history of contemporary art conceived on the Vasari model, composed by recording and collecting the interviews carried out with artists, and not only. If his first romantic hero was not the “much hated” Santa Claus but the writer of inner and outer exiles Robert Walser – to whom he has dedicated a transportable museum – in his role as an unstoppable, and sometimes cynical, important curator is the thought of Édouard Glissant: French writer, poet and essayist, famous for having elaborated the concept of “antillanity” from which a broad reflection on the notion of multiple and rhizomatic identity starts (borrowing a term made all too famous by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari).

For Obrist, the logic of the archipelago is fundamental to be considered as opposed to the logic of the continent: when there is a single, axiomatic truth, we are within a continental thought, based on a dominant logic. On the contrary, when there is no univocal vision but a dynamic succession of truths and thoughts, perspectives multiply and “Antillian” logic develops, made up of many islands in relation or opposition to each other. From theory to practice, the passage is coherent and energetic. All the exhibition and artistic events conceived by Obrist – from the legendary The Kitchen Show created in 1991 in San Gallo, to the recent Enzo Mari curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist with Francesca Giacomelli, available at the Milan Triennale until April 18, 2021 – propose mechanisms engaging, always different from each other but in dialogue with a new thought from Gesamtkunstwerk, a reading for islands that often do not stop but that develop, over the years, different ideas and innovative stages. Obrist’s is a large simultaneous circus where everything is in relation and everything is in motion, an organic complex system of our contemporaneity that grants individual meanings to stories acquiring a unique, luminous, almost Hegelian sense, if read through a vision from above, satellite.

The Kitchen Show, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, St. Gallen, Switzerland, 1991

“After Kitchen, the exhibitions I have organized have always followed the same principle: we start by talking to the artists, who sometimes want an exhibition in unusual places, other times in museums” .

Denying, since his first exhibition, all that narrative based on the idea of “curator’s dictatorship”, Obrist bases his practice on dialogue with artists and on the willingness to develop, in a dialectical way, new ideas, born not from theoretical axioms but free to evolve even under the pressure of the contingent and factual needs that each exhibition brings with it.

This first key point of Obrist’s work originates in a precise moment, in Rome. At the age of eighteen, advised by Fischli & Weiss, he decided to go and visit Alighiero Boetti. His new mentor urges him not to follow pre-established patterns like those that lead to exhibitions in museums or galleries: artists can do much more. Obrist pondered for a long time what this “other” could be. The solution was much simpler and more practical than one might expect: he realized that he never used his kitchen, he always ate out and that room had now become the place to keep books, a sort of library.

Hence the beginning of an intense dialogue with artist friends, literally at his home; the opening of The Kitchen Show was only the consequence. In three months of opening, the exhibition had only thirty visitors. Among these Jean De Loisy, curator of the Fondation Cartier in France. Enthusiastic about the project, he offered Obrist to move to Paris, thus a research path took place, in which the game and the desire to question the routine and the ordinary never failed.

Serpentine Pavilions

From Paris to London, from the first curatorial tests to the prestigious role of co-director, with Julia Peyton-Jones, of the Serpentine Galleries.

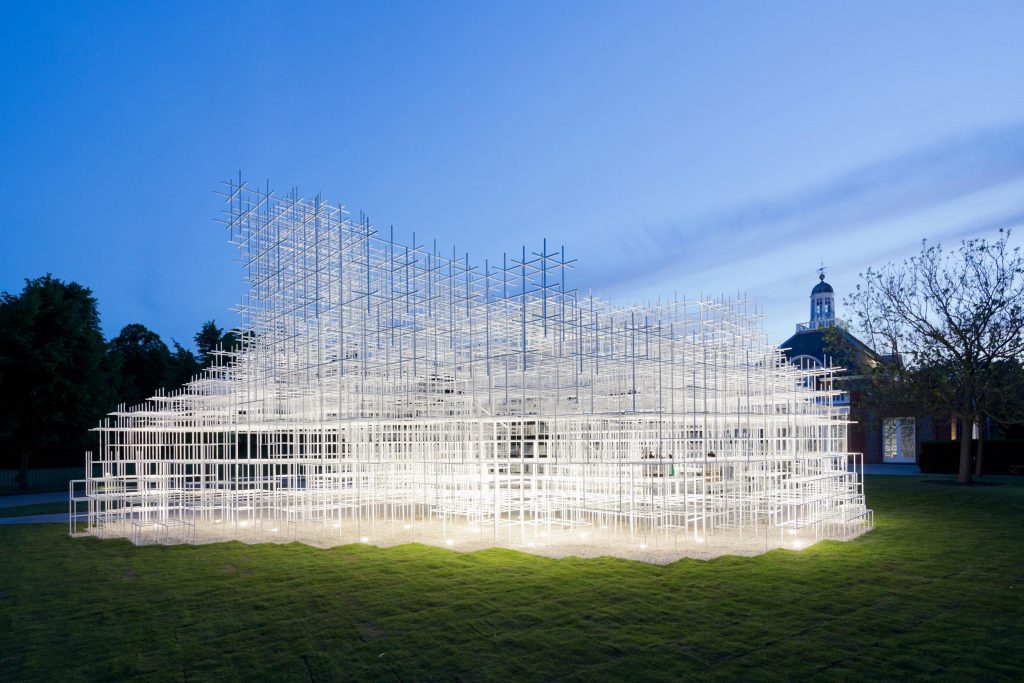

Founded in 1970, the public exhibition complex located in Hyde Park is now composed of two different buildings – Serpentine Gallery and Sackler Gallery – which can be quickly reached thanks to a bridge crossing the river of the same name. Every year, since 2000, a temporary summer pavilion has been added to these permanent structures, each time designed by a different architect. The first project was entrusted to Zaha Hadid, who built a large steel structure in the shape of a marquee. Since 2005 the architects have been selected by Hans Ulrich Obrist. Although not directly conceived by the Swiss curator, this project highlights an ephemeral approach to architecture that is fundamental to understand his concept of exhibition and the evolution of the exhibition process. The artistic event is no longer a passive occurrence that ends in a certain time and place but a broad, episodic device, open to migration and evolutionary confrontation every time it is related to different places and social contexts. There is no rectilinear time in Obrist but a dynamic of circles that influences each other in space, repeating each time different. The exhibition format changes, enters into a critical relationship with the works: whether the exhibition takes place in a minimal place like the one occupied by the Nanomuseum – a small photo frame within which to create micro exhibitions – or in a gigantic panorama like that of Cities on the Move – traveling exhibitions, curated together with Hou Hanru, which dialogue with the idea of the contemporary city – we are no longer at the source of a finite event but of the narration of stories that make up a potentially infinite episodic novel.

Photo Jim Stephenson

Museum Robert Walser

Brother of the painter Karl, Robert Walser is Obrist’s youthful hero. Rediscovered in the 1970s, he is now considered one of the greatest German-speaking Swiss writers of the 20th century. In his works the linearity of the narrative falls and the attention is often placed on details, on accidents and subjects that may appear of secondary importance. Fundamental to Obrist are the themes of exile and walks, exterior and interior, which form the guiding thread of the writer’s life and which give theoretical form to new expository attention. If the exile refers to the biography of the curator, to his escape from Switzerland, the walks become a medium through which to conceive the museum and the curatorial practice.

If with the series of exhibitions that make up the Migrateurs project, inaugurated in 1993, an analysis of the museum begins as a device that is no longer static but exploded, with works and ideas that invade every place, from offices to signage, it is in the Museum Robert Walser that we can better understand the figure of liquid space conceived by Obrist.

Founded in May 1992 as a moving museum with its starting point at the Hotel Krone in Gais, it consists of a mobile display cabinet, the kind used to display elegant goods. Thus it appears as a non-monumental, discreet building, which can be confused in the various spaces in which it is inserted. Versatile and easily transportable, he questions his own function and can dialogue with works by contemporary artists, often designed especially for him. By placing at the center the possibility of overcoming the boundary between important and not important, it highlights a precise way of conceiving the relationship between center and periphery. With Obrist, the place where a cultural event can be realized becomes a metaphor for a non-hierarchical landscape in which to walk, a panorama where the magnificence of the sunset is combined with the magic of a small butterfly placed on a flower. The museum moves because we are the ones who take a journey inside and outside it.

Take Me (I’m Yours)

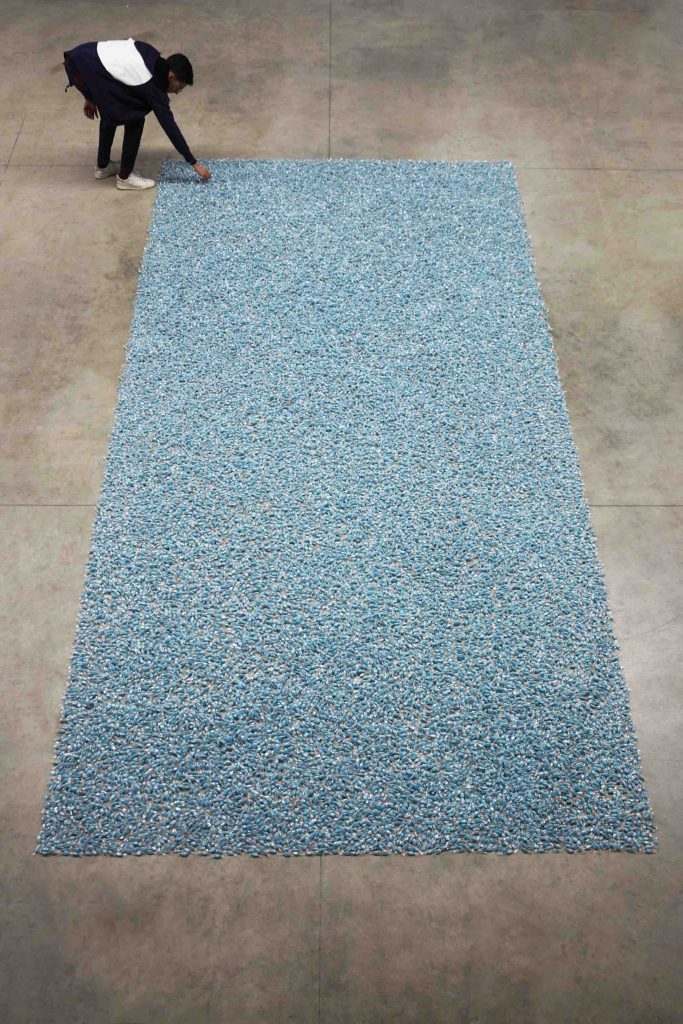

Dipped on a pile of colored fabrics. In this playful pose Obrist offered himself to the press preview of the Milanese leg of the Take Me (I’m Yours) exhibition project, held in 2017 at the Pirelli HangarBicocca. Born from an idea conceived with Christian Boltanski in 1995, the successful format offers a new way of experiencing works of art. The aura of the artistic artefact has disappeared for decades, now you can touch, modify, use and even take home with you some works present on display or made at the moment. In Milan, an elegant character with a cane loudly pronounced the name of each person who entered the exhibition hall: the spectator placed at the center of the art world.

The relationship between works, public and artists is one of the key themes of Obrist’s activity. Not being trapped in relational poetics or abstruse theories of public art, the Swiss curator proposes a key to interpretation that does not make competence and quality disappear, making the artistic experience accessible and in line with the needs of our contemporaneity. If with Take Me (I’m Yours) there is a playful discovery of new possibilities, it is through the “Do it” project that begins to redefine the relationship between curator, artist and public. The idea was born thanks to a conversation with Bertrand Lavier and Christian Boltanski, held in 1993 at the Café Select, and to the contribution proposed by Andreas Slominski to the exhibition created by Obrist, in the same year, in room 763 of the Hotel Carlton Palace. On that occasion Slominski faxed instructions through which the curator could do a new job or event every day. In the 31 days spent carrying out the indications provided, the desire to develop the theme of the instructions began to take shape through an infinite challenge to which new artists always submit. Today “Do it” is also a large catalogue in the making, a document that tells how a widespread practice over the centuries has now been problematized and contextualized, showing how the importance of a curator is not determined by the number of positive reviews or the amount of receipts obtained but from the ability it has to tell the contemporary in its making, getting its hands dirty with the news.

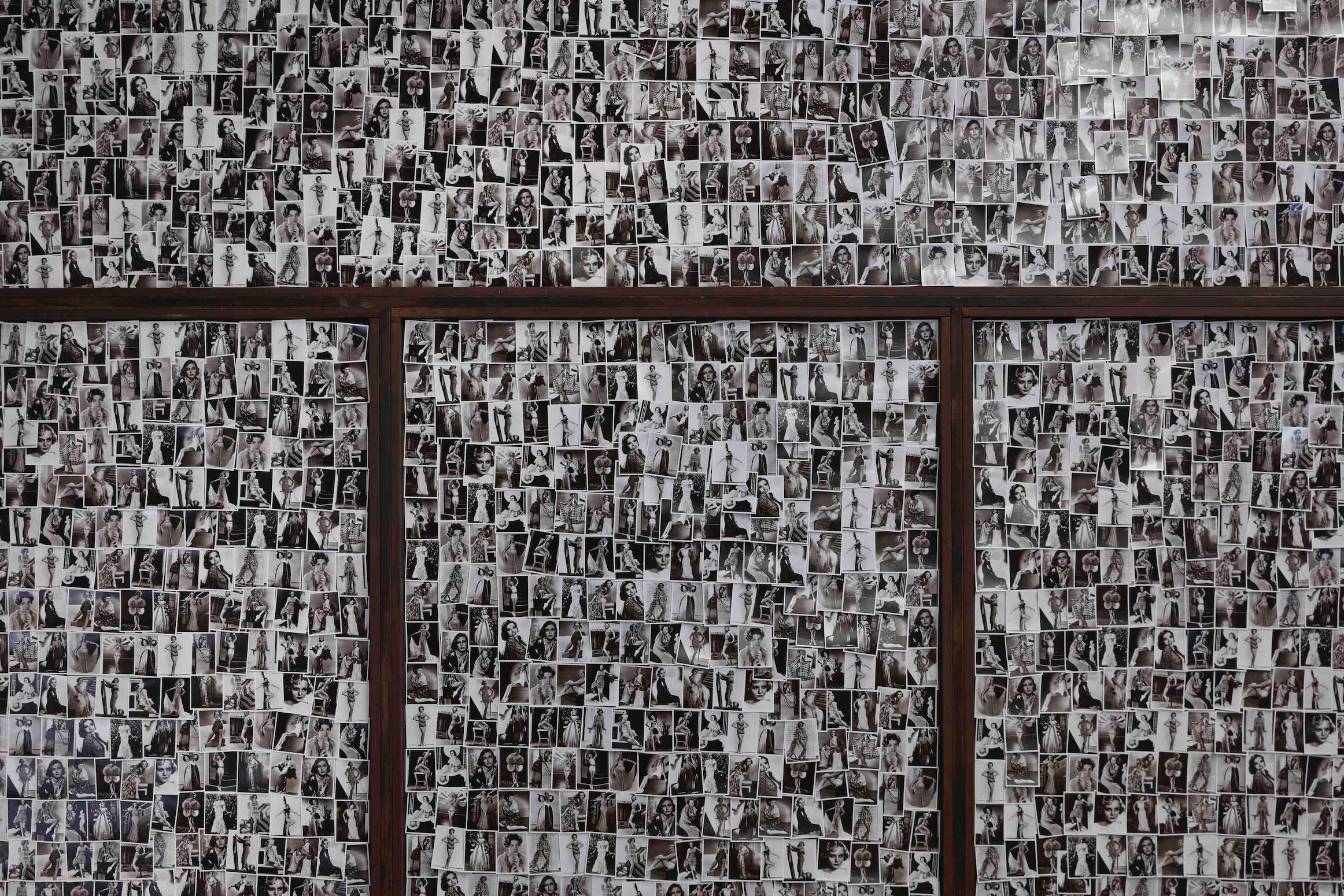

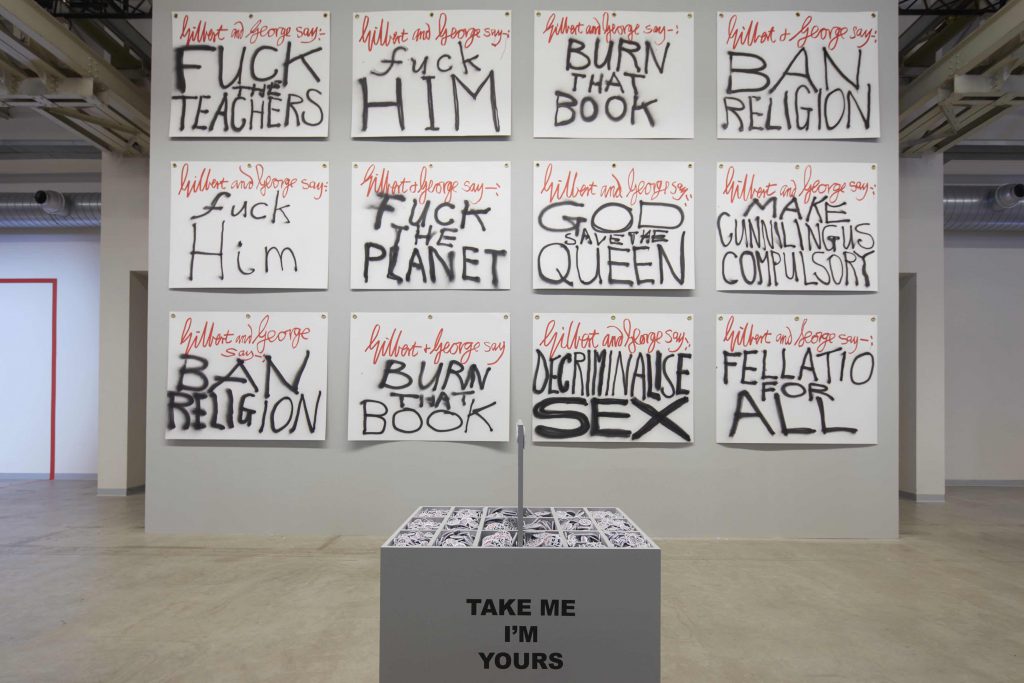

Take Me (I’m Yours) exhibition view

Félix González-Torres. Untitled (Revenge), 1991 Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2017 Courtesy Barbara and Howard Morse, New York, and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo Agostino Osio

Take Me (I’m Yours) exhibition view Gilbert & George, Dispersion, 1991-2017 Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2017 Courtesy Gilbert & George, White Cube, London and Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan Photo Agostino Osio