Archiving Encounters is a series dedicated to the exploration of archives in contemporary art practices. This series takes conversations with artists, and their practices, as starting points to encounter the different kinds of archives they choose to work with. Often artists use ‘the archive’ as a theme itself, produce new taxonomies, respond to real archival materials to critically challenge modes of knowledge production, or use it as a framing device to invent characters or events from the past that are put in dialogue with the present to shed new light on contemporaneity. This approach resonates with the practice of Alice Pedroletti, which has been presented in the previous article. Delving into the recent works of Alice, who uses the archive both as methodology and artistic practice, it explored the production of new archives, their relationships with localities and what happens when the artist works by trying to subtract part of her power over the artwork. Pedroletti proposes to see the archive as a living, fertile ground on which we can build new ideas.

If archives are often seen as hidden away, impenetrable and suspended in time, waiting to be re-activated by users, this issue explores Eat the Archives, a project that deals with an archive that was truly hidden, inside a temporarily-closed museum. Archives are the product of the social processes and systems of their time, presenting the stories of those included within those systems and reproducing the absence of those excluded. However, some stories can be discovered through these objects and can be re-told vividly through smell, taste, colour and sight of delicious dishes. This article presents the conversation with Leo Burtin, artist in residence at the Manchester Jewish Museum between 2018 and 2021. Drawing from a background in performance and theatre, Leo creates performances in institutional and domestic spaces to question notions of identity, representation, power and authorship. Food is used as a lens that helps to magnify the clues of other stories found in archival objects and as a methodology to unearth past-connections that function as a catalyst for new relationships in the present.

Portrait of Dora Black with her daughter, 1915 Courstesy of Manchester Jewish Museum

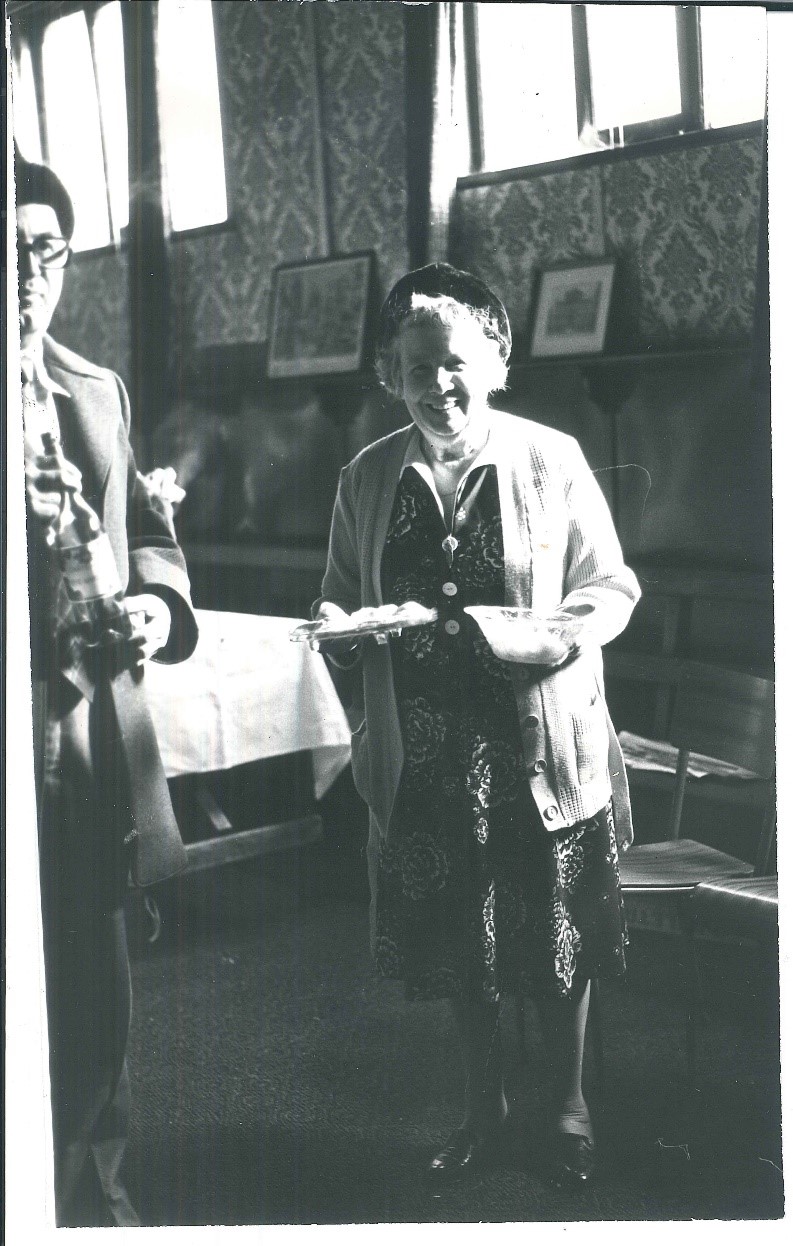

Portrait of Annie Conway

Courtesy Manchester Jewish Museum

Leo Burtin is an artist, writer and educator. Since 2012, he has been developing pieces which gently, poetically and playfully disrupt the overtly familiar act of sharing food. As a writer, he has contributed to publications such as The Guardian and The Sick of the Fringe. He is co-Artistic Director of Making Room and was the first food artist in residence at Manchester Jewish Museum. Leo is currently a postgraduate researcher at the University of Leeds, investigating the intersection of performance and food studies.

Where does a closed museum meet its archive and its community? “At the dinner table!”, it is the answer I would expect from Leo Burtin while he hands me a plate of borekas. Drawing from professional experience in producing theatre performances but building on the questions raised by artists through relational aesthetics and socially engaged arts, Burtin uses food as a methodology and as a method to tell stories and engage audiences during participatory performances.

Benedetta d’Ettorre: Thanks Leo for sharing your work with us today. Can you tell me how the collaboration with the Manchester Jewish Museum started?

Leo Burtin: I was invited to work with the Museum when their building was closed for refurbishment three years ago to find ways to animate their food related collection. They have a lot of artefacts and oral histories and objects that are connected to food because Judaism is a religion where food is of paramount importance. My role, when I began working with them, was essentially to experiment with how we might work with the communities around the museum in the area of Cheetham (ed. where the Museum is based) and in Greater Manchester to put in conversation community, food and museum practices. Over those three years, I played with lots of different ways of doing that. Sometimes we made community feasts, sometimes we organised recipe exchanges or I taught cookery classes, we just did a real range of things. We worked quite a lot with the Ukrainian Cultural Centre in Cheetham, and the museum had an exhibition at Manchester Central Library, we collaborated with Manchester Art Gallery and did a pop up event at the local supermarket. The Museum has cultivated a strong relationship with its local community but we realised that since it was closed, we were asking people from a very specific community to go to other places for these events: places that they did not necessarily ‘own’, that were not their spaces. So I started to think about how you could bring the museum to the community as opposed to bringing the community to it. An emerging interest for me was what becomes possible when a museum is open to having their collections and archives not being displayed behind glass doors. As someone who works with food as art as an artistic practice, I am very interested in the domestic and embodied relationship with everyday environments. I first thought we could host something like “Tupperware parties”, which is a business model where someone like a consultant goes to houses and hosts a party. The idea is that people have a good time with the objective to sell utensils or other goods. So I thought, how could I do that? How could I bring museum’s objects and get people to engage with these objects in a different context, for example, their very own home? The resulting project Eat the Archives was a series of dinner parties which primarily took place in people’s homes; we did a version of this in the Museum itself. Because of the pandemic, we also did an online version but online events miss all those little things that you experience together, the smell of the person next to you, the sounds and energies of being together in one room. What would happen at those dinner parties is that I would cook a three course meal that would be closely connected to three different objects, artefacts and stories from the museum and serve those courses alongside people having an opportunity to handle or interact with those objects.

People gathered during the festival of Sukkot at Manchester’s Spanish and Portuguese synagogue Courtesy Manchester Jewish Museum

B.D.: How do you choose the objects?

L.B.: It’s a very simple but complicated process at the same time. I was always in conversation with the producer and the curator at the museum. Our conversations would think about the objects on a practical level, for example, what objects you can take safely out of the archive in people’s homes. A second consideration was about what objects did not make it to the display or were less used, so the project became an opportunity to delve into the museum’s archive and make emerge those lesser known stories. Crucially for me, the question was whether the objects have a direct connection with food or have the potential to be paired with a particular dish in a way that could be interesting. After the refurbishment, the Museum’s new galleries were going to be organised according to three themes: communities, journeys and identities. They also became themes for my menus and resonated with the objects I was working with. Then it became a whittling down depending on what dish goes with what object, so that the menu makes sense both from a culinary and performance point of view. I would ask myself “does it make sense to hear that story after that story? And does it make sense to have that kind of dish after that kind of dish?”. A lot of it was very instincts-based and dialogic through quite a lot of trial and error. It was a bit like cooking, you taste something and go like “oh ok, so after I have eaten this, I want to eat this” and it was the same with the objects, once I engaged with this object, I want to engage with that object.

B.D.: How did you explore your themes through the objects? How do you construct the performances, juxtaposing stories, objects and food?

L.B.: So there is a wide range of characters that have emerged from these different kinds of menus and in a way the process of meeting those characters is similar to the process of finding the objects. It is either through direct connection or following a thematic echo. It is a process of translation and asking yourself what does that story taste like. Let me give you an example, there is a photograph with a woman holding a plate of borekas in the synagogue, which is now the Manchester Jewish Museum. At first glance, you have got this woman who is really well dressed and has a beautiful hat. She is holding a plate of delicious food during a religious festival, so you would think there is nothing unusual about that. With a little more research, I found out that this was Annie Conway, an Irish immigrant to England and she is a convert to Judaism. She became Jewish through marriage to someone else at a time where that was not necessarily easily accepted. She is there and she cooks this Sephardi food that is really quite far away from the kinds of Irish dishes that she would have grown up with. So all of a sudden this photograph tells you the story of someone who potentially tried really hard to find their place in a community that was not originally theirs. In the writing up of the story that I share in the performance I try to stay as close as possible to the facts and being as historically accurate as the records of the museum makes possible. But it is not always that easy, because these are not famous people and their lives were not recorded in a lot of detail. But I think, what conversation does this story enable me to have? Annie Conway’s story becomes a totem for thinking about belonging, conversion, to think about hybrid identities, in this case an Irish and Jewish immigrant. This story is both really specific to that one woman and that one particular object, but it could also resonate with whoever you have around the table during the performances, for something they have experienced or the experience of someone they know. Everything starts with a really specific story to move the conversation towards some quite universal themes. In this case, Annie holds a plate of borekas, so I made borekas. In some other cases it is about themes or conversations I had with my collaborators. For example I used a letter that a rabbi wrote to Jewish children that were being evacuated from Manchester into Yorkshire. Food laws are really important in the Jewish religion so in this letter, he tells them that if they can’t keep kosher, then they should keep vegetarian. This made me think of how food preferences have become a widespread conversation and really important in our time, so that letter becomes an opportunity to think about the meaning of food restrictions in any kind of context, whether that’s for dietary requirements, religion, the environment or broader economic, political and social conditions. The question for me was, how can you get a sense of tasting, connecting the sensorily experience to that place, time and story. So with that story, I paired a vegetarian dish with ingredients connected to Yorkshire. I found some cheese made in Yorkshire by Syrian refugees, so then I am able to connect the past and the present through food.

B.D.: In critical essays on socially-engaged arts, authors point at the limits of agency in participatory works where audiences are not actively engaged from the beginning but they just take part in something that has been built for them. They question the political power of these interventions, highlighting more of a similarity with the performative aspects of installations and exhibitions spaces. You talk about your work as engaging with quiet politics, how does that happen?

L.B.: After doing the research, I prepare my performances by writing a script, I test the recipes beforehand and calibrate timings. During the events, there are set times where I perform the script, however I always bring it with me and read it out loud. That is, to explicit my role and my process with the audience, I subtract some power to the performance as a place where I hold all threads as omniscient narrator. In fact, I am not omniscient and I am here reading in front of you. I don’t think there is a problem in holding power per se, the problem is how you do it. So I work acknowledging that and it is a form of constant practice for me, how to hold the power. I have a lot of power in selecting the objects and designing the performances, I also have a lot of institutional kudos that come with the project. It is like the Museum recognises my authority as a qualified person to do this kind of work, on top of that, this is part of a broader funded research project and also gets other public funding. So I am in between all of that but I do not hold all threads, just some, and I try to make them as visible as possible while offering my research into the archive. However, as soon as the audience gets in the room, we start to build together the relational space in which we will exist in. It is a dinner so people eat their food and start to interact with each other, you know, passing around some salt, jugs of water… The food works as an ice-breaker providing a matter of conversation which most people can engage with, people start to walk around to see and handle the objects, go to the toilet etc. In the meantime, the conversations develop in whatever direction people around the table take them and I think there is something quietly subversive when we offer spaces for people to become familiar with strangers and with objects that usually are so precious to be locked away in cabinets. The dinners happen in a context that offers time and space for dialogue and reflection on identity, migrations, how and what stories are told and other issues. Interesting conversations can emerge spontaneously and that is when the performance enables quiet politics. I do not like to make massive political statements that exhaust their power after they have been exhibited. I think about practising politics everyday, quietly, so if we are having a conversation using this symbol of Annie Conway’s story, that is just as powerfully political as joining a political party. The quietness comes from the fact your action is going to stay quiet but still may have more of an impact for you and the people around you. I like to build sustainable, quiet, conversations and moments that plant a seed for reflection and hopefully can be taken elsewhere and still act politically. The Museum collects objects that are tight to everyday life, so these photographs, cooking utensils, diaries and letters all came from personal belongings, they are rooted in domestic histories. I also think there was something quietly radical about taking those objects out of their glass cases and archival boxes and bringing them to where they come from.

B.D.: I would argue that all your performances are crafted so that they provide a framework for the audience to engage with, so that at the beginning you set clear roles and boundaries that keep the space of the performance existing while it slowly deconstructs these roles in favour of spontaneous emerging relations. It’s like that you curate the space but relinquish some control over it. Can you tell me more about your role as a host and your relationship with the audience?

L.B.: Through the Museum we open a call for people to volunteer to host the dinner. Some people were volunteers at the Museum and wanted to participate but others just found it by chance and decided to put themselves forward. I have to say, it was quite magical how all the people that participated were just perfect for it. Some just wanted to do something different and were generous and curious about it, some others had a personal interest in archives. Others had connections to the objects and some of the histories. For example, there is a book where a midwife recorded births in it and one of the guests had his grandfather listed in the book. One person hosted it as a way to meet their new neighbours and had a kind of excuse to be in touch with their community. What is also really brilliant about going into people’s homes is that you are not in control of the audience, the host signs up for the event but then it is their house and they can invite whoever they want. And those people are not necessarily the people who would buy a ticket to an event, right? It is a very different kind of invitation. I co-host the dinner with the people that live in the house, in a way, we share responsibility for it. In these spaces, the idea of hosting quickly becomes a blurred one. Just before the start of one dinner, I was in the kitchen preparing some things and a friend of the host came in through the backdoor, grabbed a beer from the fridge and started asking me questions and going around to greet the other guests. In a similar way, when we did the dinner in the space of the museum, we did it in a dedicated activity room that does not like a formal museum gallery but still it is an institutional space. During the dinners, guests are free to move around, chat etc, so I cannot and do not want to control that, it is up to them to construct their experience in relation to others. I know that by selecting the objects and designing the event I hold a lot of power, so for me the intention is important and it becomes a constant practice of questioning how that power is held and shared.

B.D.: A challenge for participatory works is their documentation and archiving, what approach did you take?

L.B.: There are two sides to that question. One is the at home performances, which will just disappear or exist in the minds of the people who were there. They leave material traces, for example, little menu cards and things like that. But these performances will just be allowed to disappear. There is the writing that I’m doing about it for my research project, that is also a form of documentation, but that also is going to be a kind of echo of the experience. And then there is the film which was staged, we have reshot particular angles or peoples entrances into the room. Everything was set besides the conversations that people had at the table, which were not scripted. And so that is what will stand for the project, effectively, it becomes a kind of archive in itself, a ghost of what it has been. I chose not to film the other performances to keep the value of the experience in the moment, so the film works as a methodological account to allow others to watch and understand what happened and how the project worked.

B.D.: You call yourself a ‘food artist’, where does your work stand in contemporary art?

L.B.: The question about the nature of my work, is it food, is it art or performance? It does not really interest me. What I am most interested in as an artist is to create the conditions for people to be in different kinds of relationships to the ones they normally would engage with. I have taken this work in a lot of different contexts: art galleries, theatres, community settings and, you know, strangers’ homes. I am not interested about the form but, rather, the outcome. Sometimes, it is easier to call what I do a cookery class or performance because they attract different people. I think it is a matter of class, some institutions are inaccessible to some people. Culture for me is a matter of what makes you human and it can enable you to see things differently. I think I have never met anyone who is not interested in that, so I want to try and take down barriers and engage with different people. In both museum and domestic space I collaborated with an artist called Sheila Ghelani, whose works are a hybrid between performance, visual arts and socially engaged practice. In the museum we need to prepare the space from scratch and in people’s homes I do not know what I am going to find. As a form of care, I make sure there are key objects that can ease people into the space and what is going to happen. I take care of the organoleptic qualities of food that resonate with the stories and make sure everything else fits in a comfortable environment. I would argue that her approach is visual while my approach is more word-based, so I asked her to work as a visual dramaturg and help me to find subtle ways to transform the spaces so that you are still in the person’s home but it becomes a different space perhaps a museum, since we are bringing in these objects. The space is curated so that it stays in flux between formal and informal expectations and allows different relationships to emerge in that ‘non-territory’. This could sound insane but she helped me to figure out the little details, so that people could have the best possible experience. For example, the napkins or what apron I could wear that would say ‘I am going to look after you, yes this is your home but today it is also something else’.