Born in Santiago de Chile (1979), the audiovisual artist Enrique Ramírez trained at the Institute of Arts and Communication (ARCOS), a mix of cine, video and visual arts. Then, he earned his Masters degree at Le Fresnoy – Studio National des Arts Contemporains (Tourcoing, France) high-level audiovisual arts and contemporary art. Enrique Ramírez is recognized on an international scale and his artwork rounds in fairs, festivals, biennials, institutions and museums. He works across video, photography, installations and poetic narrations. As a filmmaker, Enrique Ramírez offers a personal vision in which history, memory and the collective imaginary are played. The public must read it as an open windows of an event of the reality that concern us and interrogate our relationship with it. In spite of great aesthetic beauty by the poetry of his productions, he takes a committed position with this present rethought from the past shaped like an image. Enrique intends to rethink the common spaces taking care of the silent indices that compose them, full of narratives. In order to achieve his aims, he raises questions of great commitment with the individual, without seeking answers. The walking figure and the natural scenes are his central themes. In them, the individual is lost in a horizontal line that constantly questions the cyclical and vertical conception in which history is inscribed: superimposition of times, of spaces and of narratives. The final result is an interface that challenges and implores directly to the viewer placing him in a situation of discomfort. Visually, the exhibition’s staging is approached as a montage: a cut of scenes mixed with music, noise and voices in off that challenge the harmony in which reality is shown. In addition, public, left completely free, is asked to live their own experience. Once history is compromised, new realities and gazes submitted as appearance or simulation may be regarded. Indeed, this conception of the time like a timeless journey leads us to renew our way of seeing, as well as allowing us to envisage new readings.

Coral Nieto Garcia: While you position yourself as an artist, to what extent could your practice resemble, both in the media and in the form, with that of a historian, sociologist and / or anthropologist?

Enrique Ramírez: I come from the world of cinema, and I have always considered that my career started working as an editor. My work methodology comes from the interview, from research. So, my way of proceeding is, above all, like a documentary.

CNG: I find the relationship that is woven between memory and history very interesting. I would like you to talk about how you question collective memory by making use of history? What role does the notion of “travel” acquire in this temporal and geopolitical transposition that involves moving between memory and history?

ER: I have a constant concern in my work: how the world connects with myself and how I respond to this stimulus. In this sense, the public seems important to me. Actually, I am also part of this audience in my every day. So, I worry about the way in which the artwork can connect, in some way, to your way of thinking, to your own reflections, that is to say, to your own experience of life. Hence, my works are nourished by history and by memory. For that, my key tools are documentary, interview and research. Now more than ever, we must think about how we learn from history and how we live in a kind of loop, of light that repeats itself.

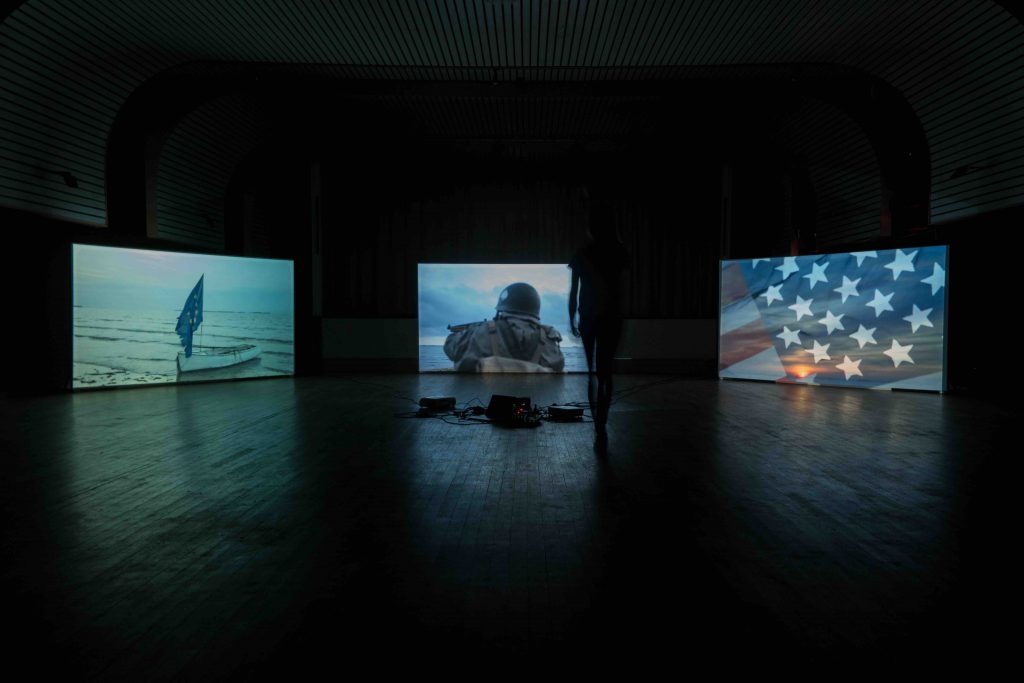

Installation view Courtesy Michel Rein – Paris/Brussels and Enrique Ramírez

Moreover, a trip is also something mental. For example, what I look for when I go to the cinema or a museum is, in some way, to be transported. It’s not about distancing yourself from the real world, but somehow traveling. A trip is not made only physically, but the connection that exists between the work, the spectator and the artist. In a manner of speaking, my artwork should be understood like a triangle or a candle, three points that come together. Once these three points merge, the work makes sense. On the contrary, when I see a triangle that tells me nothing about my relationship with the world, this geometric figure becomes simply abstract lines that come together.

CNG: In your artistic practice, the montage process acquires a conceptual, aesthetic and technical form. What expressive force do you see in this spatial and temporal process? How does this tool work to reinforce the interaction between the viewer and the filmic material?

ER: As I said before, I worked a long time as a filmmaker in the world of cinema. At the time of the exhibition, what I try to do is “cut” as I do in a film. Each work is like a scene, and all of them form a movie or an idea. It is important to me that the viewer can conceive his own film through his own vision and ideas. The viewer must live the route proposed in the installation as a montage, as a set of cuts, in which each scene acquires a sense within the complete set that is the exhibition.

However, in the world of video, montage is a general problem in the sense of temporality. What I mean is that when the spectator goes to the museum they spend much less time than when he goes to watch a movie at the cinema. The relationship between body and space is very different. We have a kind of “memory”, and our relationship has been impaired. The video needs special conditions in the museum so that the viewer can feel comfortable.

Enrique Ramírez. Restos de mar, 2015 Photography Courtesy Michel Rein – Paris/Brussels and Enrique Ramírez

CNG: The French philosopher Jacques Rancière, professor of politics and aesthetics, accords great importance to the partage du sensible (the distribution of the sensible). According to him, the real must be fictionalized through the collective imaginary of history in order to be rethought. Do you identify with such considerations?

ER: Yes, I do, because history takes an important place in the future and in the present. When the artist reflects on the problems of the world, he automatically has a personal vision, but integrated in a global vision. However, it should be noted that an artist cannot deliver answers, but creates questions. He must open a window that gives to see and leaves you free to draw your own conclusions. In fact, the art that interests me is art that is able to ask relevant questions to the current situation in our world.

CNG: Throughout your career there is a recurring interest in the figure of the walker and his environment, especially the sea. To what extent do you want the viewer to identitfy with this figure?

ER: In general I am interested in the reflection that there is about walking, the fact of moving forward and its relationship with time. It is a very important philosophical question in a world in which our way of life works too fast, bombarded continuously by images. We can think about how Google and algorithms handle our entire way of thinking. The idea of walking, which is also represented in the sea, is overall slowness. We have the necessary time to look to the sides and establish a horizontal, slow and reflective vision. Today we do not travel, but we move. And the walk or the trip in the sea, still provides us with a place of escape: to travel from one place to another, to go to a place, where the idea of transit becomes essential. It brings to me the work table of my father, flat and immense, “cutting” vertically as movies were made in the past.

CNG: Could you tell us about the projects you are currently working on?

ER: On the one hand, I am currently working on the project Tidal Pulse, Part II for the Norwegian Screen City Biennial (SCB) that will take place during its opening weekend (October 17-20). For the present edition Ecologies – lost, found and continued, this project allows me to focus more on the world of sound and not so much on images. The travel I proposed is a site-responsive sound piece and visual voyage taking place on a local tourist boat in the port city of oil pumps, Stavanger. The boat travels through the Norwegian Fjords for a journey of approximately 3 hours. It is used like an oscillator that composes music: I recorded the underwater noise of oil pumps and the sounds of the boat – the vibrations created by the engine inside and outside the moving vehicle and in the operations room. The whole is like a sound source piece that becomes the boat’s pulse, and intertwines with the voices of local people who are committed to climate change from different perspectives. They encourage us to reflect on the world in which we live. The public is invited to hear this boat that contaminates and produces this musical composition during the journey. On the other hand, at the beginning of October I will present the exhibition Mar, mar mar (Sea, sea, sea) in the Michel Rein Gallery in Paris. The display, as the choice of title indicates, sets a constant problematic that comes around the sea: it is about the Mediterranean, the flows, the migration.

Enrique Ramírez. Los durmientes, 2014 Film, 4k, 3 screens, sound Courtesy Michel Rein – Paris/Brussels and Enrique Ramírez

CNG: Taking into account that there is a common theme that resonates throughout your artwork, what relationship or starting point is this new project established in your trajectory?

ER: It is more like a return to the past. Before studying film I studied at the music conservatory for six years. While sound is something that has always been very present in my work, I have reached a point where I need to abstract from the image. But also it is a question of language: music goes much further than a video which is always conditioned by time and you do not need to speak a language to understand it.