Treti Galaxie is the tight artistic-curatorial co-working of Matteo Mottin and Ramona Ponzini. Based in Turin, but set in a virtual third dimension, the ideas’ one, their project is actually a state of mind rather than a concrete place. The aim is to break boundaries between curatorship and art, choosing to investigate the spaces in between, developing a conceptual “galaxy” of intense collaboration and choice, focused on artists’ works, where ideas are enhanced to stream in both directions.

The duo doesn’t have a fixed and preferred location for the artists’ programs they decide to follow, but are used to tracking down venues that are more suitable from case to case. Whether definitions are usually strongly pursued, this time might be useless and unprofitable to enclose Treti Galaxie in a specific category.

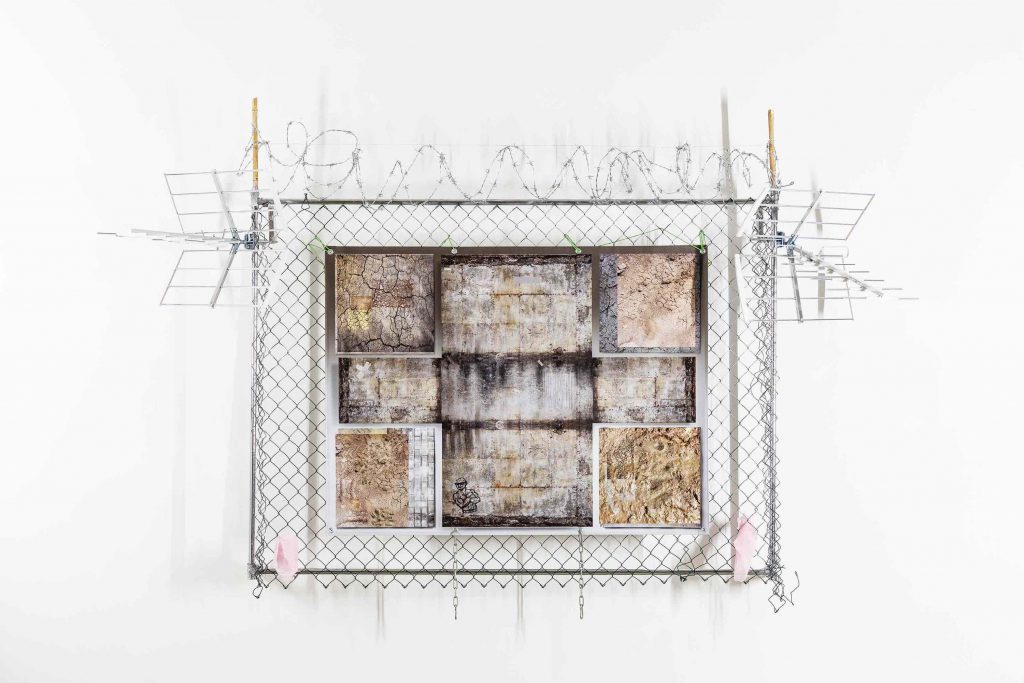

It has recently closed the latest exposition curated by Matteo and Ramona, Giuliana Rosso’s show in Veda, Firenze, where a painted and turned upside down vault lays on what used to be the gallery floor; a floor which had been devastated in the 1966 flood of the Arno. The installation looks like the image of an ideal frescoed ceiling reflected on the surface of the water that once flooded the space.

Since we had the chance to interview Matteo and Ramona, we are going to let themselves better explain how their project had started and which are the main principles that stand behind their work.

Photo Flavio Pescatori

Giulia Perrucci: How did you meet each other and how did the idea of Treti Galaxie come to you?

Ramona Ponzini: We first met during an opening at Norma Mangione Gallery, in Torino, in September 2015. We had never met before, but we smiled at each other and the very day after we met again, a sort of date, and that night we decided to create Treti Galaxie, began working together, became a couple. It all happened really quickly, as love at first sight. At that time, Matteo was writing a lot of interviews and he had already curated two shows.Matteo Mottin: The first one was at Barriera, Torino, the second was a secret show I curated in a subterranean cave in Sardinia. It’s still on, and it’s only meant to be experienced by the objects that are there, and not to be seen by human beings. Two months after I had met Ramona I curated another show at Museo Casa Mollino. In January (2016) we started working on what Treti Galaxie would become.

Giulia Perrucci: What were you doing before Treti Galaxie, and what are your professional backgrounds?

Ramona Ponzini: My sphere of studies is actually Japanese culture, as I graduated in Japanese language and literature, and spent two years of my life in Tokyo. I’ve also been playing and carrying on an artistic research on music for a long time, related to the study of the musical potential of Japanese poetry, releasing many records and touring. Then I started working in the project management field. Matteo Mottin: I am a mechanical engineer, with a Master degree in Materials Engineering from the Polytechnic University of Turin. Almost at the end of my studies I went for the first time to an art exhibition. It was a Francis Bacon show, and it was stunning. I stayed there for three hours, completely dazed. Telling the truth, I think it was the first time I saw a work of art in my life. After that, I just quit university, I was into this recent discovery, only interested in seeing exhibitions. I started doing several interviews. I learned all I know about art thanks to these conversations with artists, curators, gallerists. One of the most significant interviews for me was the one I had with the Brazilian artist Tunga. He was such a kind person and an amazing artist, building a complex but extremely coherent world, where every phase of his work was a focus on a part of the whole, and in the end everything works perfectly together. Speaking with him was a very dreamlike situation.

Giulia Perrucci: What is your idea of curatorship and how it dialogues with artworks?

Matteo Mottin: Curatorship, from our point of view, should work on the time and space that stands between the spectator and the work of art. We investigate the movement in both directions, there is not just one way. The spectator moves close to the artwork but also turns away from it, goes back home, has dinner, goes to bed. The time that it takes to forget the show is also part of our research. There are actually three kinds of research: the practical and physical one in the place we are going to work in; the theoretical one, which happens after the project is done, so not to affect the artists, since we often understand what we have achieved in a project after it’s done. We prefer the artists to have an unmediated relation on the theoretical level, so that they can reach what they really want. The last type is the daily and continuous research, with studio visits, that is the base of everything. An essential point for us is to overturn the anthropocentric point of view – otherwise we will be stuck and soon destroy ourselves. We think art is self-sufficient, and it doesn’t need to be approved by other people. The public is not essential to determine a work of art. We don’t really know if what we do has worth for other people, but it is for us. Once, we had a show for just one person, selected at random, so we are not really into the commercial side. Things stay there anyway, if you can’t “hear” them it is a sort of problem of yours. We help you to experience the work of art, but it lives forever even though not seen.

Giulia Perrucci: Can you say something about the projects you have worked on?

Matteo Mottin: If you look at our projects, the thread that runs through them is the idea that artists in the future will move from doing artworks to creating experiences.

Our first project was with Valerio Nicolai, an amazing Italian painter from Gorizia. The idea came up during a dialogue with Valerio, we were totally drunk. I was reading a lot of object oriented ontology stuff, like Graham Harman, and thinking about how to overturn the perspective of an art exhibition. I remember Valerio told me “I want to see a bird moving on my canvas”, and we started from there. The next show started as a joke, with Michele Gabriele and Alessandro Di Pietro. They sent me a vocal message saying “we have to do a show called Tiziano and Giorgione”, which was indeed our second show, set in Barriera. More than an exhibition, Tiziano and Giorgione is an intense dialogue, a sort of blood bond they signed, which is linking them still now and it will until they’ll die. Both of them have a secret notebook with the will for the other one in case of death, as a kind of testament.

Giulia Perrucci: What persuades you to begin curating and following a project?

Ramona Ponzini: Before starting a new project, we ask ourselves if there’s really the need for the existence of another exhibition. Do we need another proposal among the ones that are there already? If the answer we give ourselves is yes, we try our best to do it.

Matteo Mottin: At the same time, we ask ourselves a question regarding the artist we’d like to work with. If all the people on the planet would disappear tomorrow, and this artist would be the only person alive in the whole world, would she or he still keep making art? We look for genuinely obsessed people. Since artists are people that dedicate their lives to create something that will outlive them, and since they wouldn’t know all the people that will outlive them, we think it’s fair to start from this perspective.

Giulia Perrucci: You mention Queneau’s Esercizi di stile in a previous interview for Flash Art in 2017, when speaking about your work, could you explain in further detail what you meant?

Ramona Ponzini: Esercizi di Stile was translated in 1983 by Umberto Eco. He’s a big reference for me, since over the years I have translated many books from Japanese into Italian. In that amazing book, Queneau writes the very same story, a quite banal event from daily life, in 99 different literary styles, as if experienced by 99 different people with 99 different backgrounds. So, 99 different glances on reality produce 99 different stories, and what really makes them unique is language. In that interview, Marco Tagliafierro was asking us what differentiates Treti from other art projects, and by quoting Esercizi di Stile we were just supposing that all the art projects he was referencing to in the question are immersed in the same time, and the output they produce may be the very same story, but seen from different perspectives. Like the prism in Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon.

Giulia Perrucci: Ramona, how do you deal with your artistic work on one hand and the curatorial on the other?

Ramona: Basically I reached art not because of my professional background, but through music, as I started playing many years ago, basically experimental music, whose genre is not confined. Throughout the years I have met musicians with similar points of views, who started to experiment themselves also in visual art. For example, Christian Marclay, whose work Record Without a Cover is exactly a piece of art: it’s concretely a vinyl, but you can touch it and experience it. It breaks the ritual of vinyl lovers (records must be touched the least amount possible!). But when you play it you can hear the result of the physical contact of people who have experienced the record. From him I started studying and approaching visual art. I had a break in producing music, then I met Matteo and we started the curatorial project, and later I felt the need to restart doing music, but in a different way. Last month, I performed an homage to Salvo at Norma Mangione Gallery. I tried to communicate the painter’s work, but in a different way; what I did was basically a mediation, which is the work we are carrying on with Treti Galaxie; so I can say it definitely influenced my work as an artist.

Giulia Perrucci: Would you like to enlarge Treti Galaxie in reality, or do you think the dimension of the duo still fits your goals? What are your plans for the future?

Ramona Ponzini: I love the idea that a “baby” Treti Galaxie is going to grow. We don’t exclude the idea to have a fixed place, but it would be part of a bigger project. Things move too fast, and being a container for us looks like being in a trap, it wouldn’t be fair to the artists. When you have a place you can’t have all the other ones anymore, so if we will ever have a space, it would be a part of a larger whole. Since time and space are tight and relative concepts, if we’d open a project that needed a building, it would just be a piece of our puzzle. I’m not so sure about enlarging our team, it is very different to share the same point of views, which doesn’t mean we don’t argue.

Matteo Mottin: Concerning plans for the future, we are willing to organize a Robert Morris retrospective exhibition, gathering all the felts he made in his lifetime and installing them on the International Space Station, finally freeing them from the burden of gravity.