Is there something we can call natural? Human activities altered nature forever: earth, water and air are different from some years ago and they will never be the same. From the discovery of agriculture, humans improved plant production, selecting seeds, changing their habitat and creating new species. This is the Antropocene era: nature has been so stressed by humans that it dies or finds new ways to survive. In his artistic research Luca Petti (Benevento, 1990) explores the relationship between human activity and nature, to point out the processes behind the practices of production and their relations to the environment. He imagines a close future where animals and plants evolve, creating new relations with other species and the environment. His sculptures weave together research, imagination and harmony.

Gianluca Gramolazzi: The term Antropocene became mainstream just a few years ago, with the raise of Fridays for future, an international movement of school students, led by Greta Thunberg, who demands action from political leaders to prevent climate change and for the fossil fuel industry to transition to renewable energy. However, the theoretical discussions about Anthopocene started in the end of XIX century. When and why did you meet with Antropocene?

Luca Petti: I started a focused investigation into the Anthropocene in 2016, when I realised that my focus on the plant world was not just an interest, but an important part of me and my conception of life. It was in that year that I started collecting plant species from Madagascar, Hawaii and other parts of the world. I needed to study them, to understand the relationships and complex geometries that made them up.

G.G.: Which plant do you have? Is it an ongoing field research?

L.P.: I own a lot of plants, about 50, all belonging to the apochinacea family, the species specifically called pachypodium.

I am cultivating and acquiring all the sub-varieties of the species, from lamerei to brevicaule, from eborneum to namaquanum.

The research is based on the form, aesthetic-functional qualities and survival and adaptation characteristics of the species, which is currently poached and sought after by collectors worldwide. This spasmodic and reckless search for the species, mainly by the Eastern world, is leading to the disappearance of the plant in endemic territories.

Several aspects are concentrated in my artistic practice and research: the aesthetic one, the study of functional characteristics for the survival and proliferation of life, and the market – legal and illegal – hidden behind the plants.

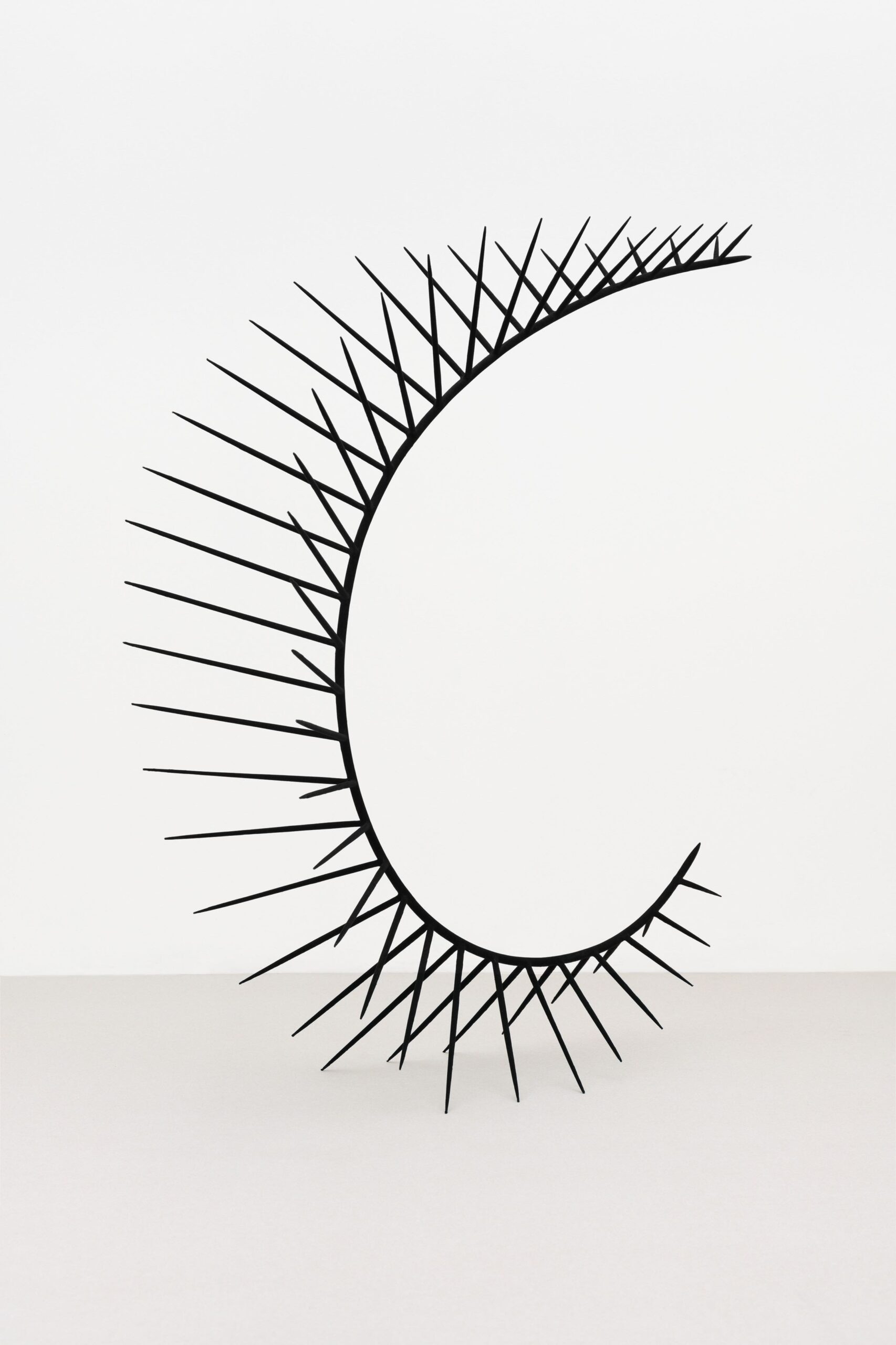

Luca Petti. Albina Crestata, 2021 Photo Rafa Jacinto. Courtesy the artist

G.G.: As Timothy Morton wrote on Hyperobjects, the climate change is seen only for its effects: we can perceive the rain, but not what caused it. Sometime, staring to the woods, I look for imported species and I think about their effects in a new environment. They grow in a place where everything is different, where there are new enemies and allies. The relation is also the starting point of your artistic research. Why is it so important for you?

L.P.: Relation for me is a fundamental character because it is the reason that determines the survival of a species. Plants, for example, are an organism that appears totally immobile to human sight; they are sedentary life forms that have chosen to weave close connections with insects and animals, creating relationships of dependence and interdependence from which they derive nourishment, movement of material and reproduction. This coexistence is the key to the success of plant species, the first inhabitants to appear on the planet, so I believe they are the fundamental cornerstone for the potential future of humanity, for the success of life.

G.G.: The changes are quick, we can’t stop them. And it makes me feel anxious. Despite the heaviness of the subjects, your artworks are calm and funny. Is this a strategy to keep the public attention?

L.P.: There is no strategy, my works take as reference hypothetical future scenarios of an extremely resilient nature that, despite the constant changes imposed by man, manages to renew and recreate itself. Certainly the coming events that await us are not the most optimistic, especially for the human species, plants and animals will re-establish their cycles, forming new alliances and creating new symbioses with ever more extravagant forms to adapt to future contexts and conditions. In my practice I imagine possible future combinations from the data we now have available.

G.G.: Your last exhibition at Palazzo Brancaccio, curated by Contemporary Cluster, show your last cycle of artworks: Materia esotica (exotic material) Could you tell me something about it?

L.P.: Materia Esotica is an installation comprising several works, a site-specific display set designed for the spaces of the palace. The project reflects on a hypothetical dystopian future where, due to the total desertification of water, the organisms that remain alive – plants and animals – must adapt to a new condition of displacement and nomadism. Forced to abandon their sedentary ways, they arm themselves – in this acid yellow scenario – with prostheses, plastic inflatables and new structures to support the continuation of life on the planet.

There are many references to the current destructive and brutal human actions. The work “Nel tentativo di tornare a nuotare” refers precisely to the reckless hunting of shark fins – currently ongoing – used in oriental cultures as a medicine, an aphrodisiac or simply as an ingredient for typical dishes. The living animal is deprived of a fundamental part, essential for its survival. Its death sentence is thus signed and it will be marked by a long agony. And it is at this moment that the fin, just cut off, chooses to evolve, transforming the nerve endings into legs, an action that defines future amphibian paths.

G.G.: In your artistic research you used different kinds of material, shaped with many types of techniques. Would you tell me some of them? (sottolinea l’aspetto artigianale del tuo lavoro che mi piace molto ❤️)

L.P.: The use of non-canonical materials and techniques in sculpture is part of my artistic process. I observe and study new and/or different applications of materials every day. An example would be bismuth, a heavy and fragile metal, which is part of the sculptural group ‘Materia Esotica’, or the experimentation with galvanic tropicalisation processes.

I use materials that are able to reinforce the concepts I wish to convey through my artistic practice.

Another important technique is velvetting or flocking, an electrostatic process that allows the fabric powder that I apply to the metal supports of my sculptures to be placed vertically. I also use the cast technique, which I use to reproduce plants and animals with the aim of finding new assemblages and combinations.

G.G.: What’s your perspective about the future of Antropocene?

L.P.: I don’t have a good feeling about this, unfortunately we are profoundly stupid individuals even if we define ourselves as the most intelligent beings on the planet. In this regard, I am reminded of Adam McKay’s character-driven film ‘Don’t Look Up’. A meteorite is about to hit the earth but until the final moments no one believes that this is possible, not even in the face of scientific and visual evidence. This film production for a wide audience led by Leonardo Di Caprio highlights how climate change, which has been talked about for at least 20 years, is a highly underestimated phenomenon even though it is there for all to see. Now that the phenomenon is blatant and obvious even to the most foolish, there is still no reversal. My works similarly exasperate and reveal an alternative nature of near futures based on the choices that have marked the evolution and downfall of humanity.