Shehrezad Maher was born and grew up in Karachi, Pakistan (1988) and currently lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. She studied visual arts at Bennington College (2011) and received a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Yale School of Art (2014). Her practice spans sculpture, video, installation and performance. Recent exhibitions of her work include a solo show in Karachi, Pakistan (Hover/Hum), several public intervention projects in Karachi, and group shows and screenings at Flux Factory (upcoming, Queens, New York), Regina Rex (New York, NY), Storefront Ten Eyck Gallery (Brooklyn, NY), Temporary Agency Gallery (Queens, NY), The New Filmmakers Series at Anthology Film Archives (New York, NY) and Twelve Gates Arts (Philadelphia, PA).

Francesca Pirillo: What are the most important influences that have moved you as an artist? Why do you make art?

Shehrezad Maher: I have always wished I was a musician. Growing up, I surrounded myself with instruments, wanted to be good at playing them and make music somehow. However, my interest in music far exceeded my talent. I excelled in art academically but I didn’t take any particular joy in making it while in school. I had never really seen contemporary art until I journeyed to New York and made my first dedicated trip to MoMA when I was 19. Quite suddenly, a whole new world opened up for me. I understood the language of what I saw, even though I didn’t understand how or why I understood it. Art became a way for me to try and move closer to the immediacy and emotional effect music has on me, without needing to become a musician. As I came across art and music that really moved me, the desire was created to have that effect on others.

This feeling occasionally emerges also when I read great literature. I have recently been reading Anne Carson’s writing which I find really beautiful and I aspire to that ability to communicate so many nuances and previously inarticulate moments with one simple gesture or word.

F.P.: Your work intrigued me in that you have not focused on a particular medium. Your practice extends between sculpture, video, installation and performance, but the medium seems to be rather in the service of an idea, central in your poetry. Do you think so? How do you get from idea to final product?

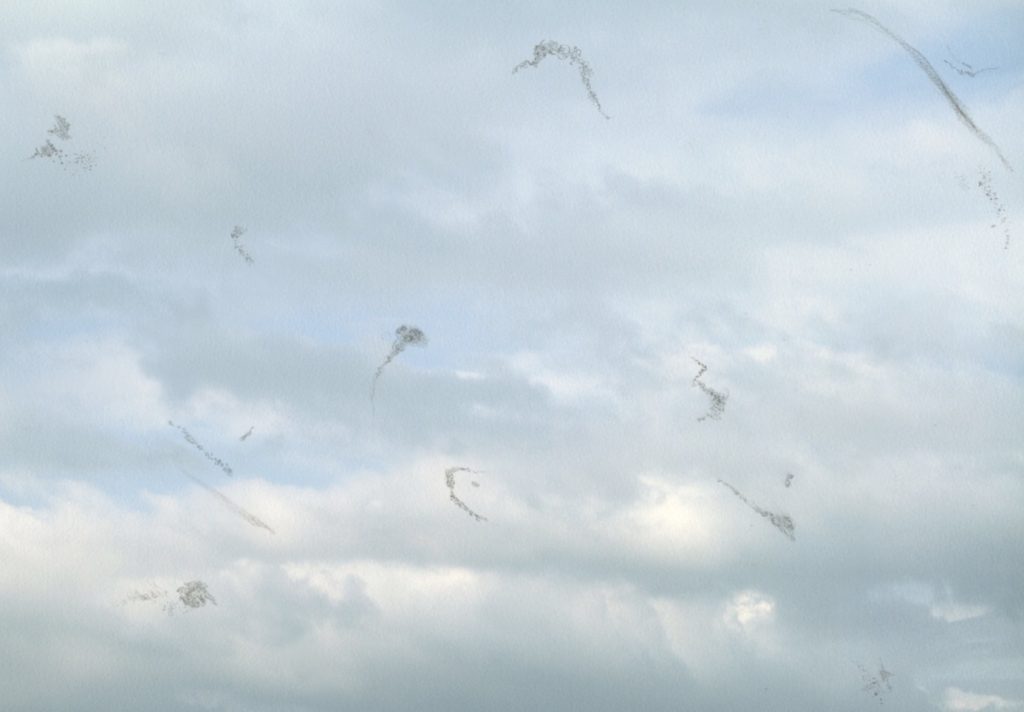

S.M.: I agree. I am in constant pursuit of a productive relationship with the instability and doubt that is inherent in committing to multiple mediums and ideas. I also value uncertainty about how or when my work is to be viewed and moments when viewers make small decisions where they don’t generally expect to make them. I don’t think of the works as final products, but rather as variations on ideas that are constantly evolving or devolving. Sometimes the work is impulsive and happens quickly, as in the case of Paper for a Cloud and Winter Sodium Self. Every time I think I’ve identified the trajectory from an idea to a piece, the pattern changes. Sometimes months will go by working tediously on another carefully planned project and its carefully assorted set of confusions, and out of nowhere a rogue idea will burst forth through the proverbial kitchen door of my belabored mansion plans, dancing and singing and almost bumping into and crashing all the porcelain and china. Multiple projects play off of each others energies and ideas, sometimes fantastically, sometimes miserably.

F.P.: You have lived in many different cities, your training has obviously been influenced from that. What did you bring with you artistically from each of these?

S.M.: In Pakistan, I was schooled quite conservatively in realistic painting. At Bennington College, VT, I slowly lived my way into values I still hold dear – that I don’t need to declare an allegiance with any one medium and that developing a style was not a very interesting goal to begin with. I was surrounded by incredible artists and mentors and this slowly helped me shake off the rigidity of my training in Pakistan. The image that comes to mind when I think about this is of a dog vigorously shaking water off its coat after a long, reluctant bath.

In Berlin, I realized the importance that walking had in my processing of ideas.

And I think the best tools for criticality, self reflection and learning to trust myself came from my intense two years in New Haven as a graduate student at the Yale School of Art, where I met some incredible people with whom I still have conversations that help move my ideas and art along.

F.P.: What is the message behind each of your artistic features? I am referring to your play with the natural and atmospheric elements and status changes, like in the artworks Paper for a Cloud, 24.8°, 66.8° — 41.3°, -72.9° , Winter Sodium Self…? Tell us a little about these works.

S.M.: The works don’t have a message, or defined goal in mind. With a lot of works, especially Paper for a Cloud, I’m still uncovering what my desires were to make them. Oftentimes I follow through on my instinct to collect or make something without really understanding why at the time. There are days when that feels like the primary challenge of making art; trusting your impulses, and moving forward with them when you’re in a state of not-knowing.

The works don’t have a message, or defined goal in mind. With a lot of works, especially Paper for a Cloud, I’m still uncovering what my desires were to make them. Oftentimes I follow through on my instinct to collect or make something without really understanding why at the time. There are days when that feels like the primary challenge of making art; trusting your impulses, and moving forward with them when you’re in a state of not-knowing.

24.8°, 66.8° — 41.3°, -72.9° is a work that consisted of six warm mist humidifiers that released a mixture of distilled water and salt from the sea I grew up near in Karachi, Pakistan, which I had my sister mail me. If you were around the humidifiers long enough your lips could start tasting the salt in the air. It was an ‘instant mix’ or ‘instant soup’ created from salt which, in Pablo Neruda’s words, is the “dust of the sea.” In retrospect, I think I was going through a brief spell of homesickness for that sea in particular.

These atmospheric elements refer potentially to the sublime but the execution of the work and the way in which it manifests is quite anti-sublime and possesses a day-to-day quality and sense of failure from the outset. To use Werner Herzog’s phrase, they were exercises in the “conquest of the useless.”

F.P.: You have also produced public interventions. How have you used street art? Tell us about this aspect.

S.M.: I think my tendency to work outside in Karachi came from my frustration with the very conservative programming and structuring of gallery spaces in Karachi. Three projects done there (Color wheel for the city, The birds only come down to the city when there is a death, and If you imagine yourself as a rock all your troubles will fall away) involved breaking a lot of rules; they were covertly done right before dawn, when the painting of public surfaces, cleaning and re-filling a large abandoned fountain pool or the scattering of 60 pounds of bird seed could go undetected.A lot of that confidence for breaking those rules comes from having grown up there and knowing how to test the threshold of just how much I can get away with. Besides enjoying the freedom I wouldn’t have had in a gallery space, I am genuinely fascinated with the stories that certain parts of Karachi tell. It is rapidly spewing forth stories and histories which go unrecorded or neglected. It creates a special kind of anxiety, joy and fear in me as an artist. That city makes me feel like a child greedily stuffing an infinite amount of sad magical marbles into their small pockets.

F.P.: What artists have influenced your body of work?

S.M.: Recently, I have been particularly inspired by Guido van der Werve, Pierre Huyghe, Ragnar Kjartansson and some of Allora and Calzadilla’s work.

F.P.: Tell us about If you imagine yourself as a rock, all your troubles will fall away.

S.M.: If you imagine yourself as a rock, all your troubles will fall away was a painted variation of a quote by painter Agnes Martin that was taken from her writings in The Untroubled Mind (1972). The sentence is simultaneously didactic and cryptic and was meant as a sort of mysterious and briefly appearing inscription on a road that runs parallel to the sea shore in Karachi, Pakistan.

IF YOU IMAGINE YOURSELF AS A ROCK, ALL YOUR TROUBLES WILL FALL AWAY / Road painting

Karachi, Pakistan

2012

F.P.: What are your thoughts about the art world?

S.M.: It depends on which art world I was to think about because each city I’ve been in has revealed such a different art world to me.

It is most legible from a moving vehicle and has a tone that is both alienating and confiding – a post-it note of sorts to a home city, right before leaving it at the end of a long visit. Sometimes, works like that and the color wheel are dedications to close and inspiring friends and in the case of this painting, it was also accompanied by the sadness of having to depart again and a desire to mark the city in some tactile way before leaving.

F.P.: What has been your most rewarding artwork?

S.M.: I think right now it might be Dimensions of a Fish. It was my first video and it still throws uncomfortable questions my way that I struggle with. With time, it ever so slowly reveals the logic of certain instincts I had while making it that I didn’t understand at the time. It helped develop a kind of atmosphere in which a lot of the following works were made.

F.P.: What are your thoughts about the art world?

S.M.: It depends on which art world I was to think about because each city I’ve been in has revealed such a different art world to me. But one thing I would love to see less of in these worlds in general is lengthy wall texts – explanations of the art or patronizing intellectual prepping and pre-conditioning of the viewer before they even encounter the art.

F.P.: What are you working on now, and what are your plans for the future?

S.M.: I’ve been slowly developing ideas for a series of small sculptures, reading a lot, and making small drawings. I recently moved to New York and the dust from the transition has only recently settled. I hope to continue staying here for maybe two more years and then might entertain plans to move to Berlin. Either way, I want to continue making art wherever I end up.