Daniele Martignoni (b. 1978) is an Italian artist based in Paris. Between 2001 and 2005 Daniele Daniele began his training in the studio of the Parma-based artist Giuliano Ziveri, while at the same time he obtained a degree in political sciences. With this duality, his researches started from an inner unavoidable need to focus on the wider anthropological concept of “human”, from its figurative representation through drawing and oil portraits. Yet, a peculiar fascination for new technologies and digital art techniques marked his poetic, consciously settled in our controversial time, far from any futile anachronism and where machines are powerful meanings for art to spread onto endless possibilities. He exhibited in several solo and collective shows, in Italy and France.

Caterina Frulloni: Your decision to devote yourself entirely to art has marked a crucial detour in your life. In facts, observing your works, – they emanate a subtle, perturbing and subliminal need. How did you come to terms with this urgency and how did your artist’s career start?

Daniele Martignoni: The urgency, I really like the term because it reflects a pressing need at a particular time in my life. I was in that so-called post-adolescent stage – I’m talking about the late 1990s and early 2000s – where I felt the need to direct an energy that was meant for something. Probably my ‘good fortune’, was indeed to stop and listen deeply to myself, and while this happened I had a pencil in my hand, realising that I could spend hours and hours drawing. It was the medium through which everything calmed down and allowed me to express something coherent through my thoughts, and the extraordinary thing was that it came to me then as it is now: naturally, without pushing.

Later, I am talking about the early 2000s, I was studying art at the atelier of the Parma-based artist Giuliano Ziveri and at the same time attending courses in political science at the University of Parma, where I would later graduate. In other words – my focal interests were directed towards artistic and humanistic studies. This has remained unchanged: my artistic research is still nourished and confirmed by reflections deriving from philosophical theses.

A significant anecdote for me was an exhibition I attended in the autumn of 2004 at the former GAM in Bologna, which was entitled ‘the Nude between Ideal and Reality’. I knew what I had to follow, a feeling that had sprung deep inside me, which I couldn’t name at the time. This wasn’t caused for sure by the classical notion of ‘Beauty’, as intended by the ancient Greeks, because nothing of harmonic or harmonious were present there, in what I was observing.

Looking at the paintings of Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud and Egon Schiele, nothing at all was pleasant for the eyes and the senses. I felt that I had to go beyond the concept of ‘Beauty’, to give form to what is called sublimation. I perceived in these works something that, by disrupting this harmony to the point of disquiet, provoked a ‘disorientation’, something authentic and therefore worthy of be considered as fertile ground for my artistic practice.

C.F.: Your creating process is peculiar and innovative, strongly linked to the present, especially regarding the leading role that technology plays in your production. How does this experimentation begin and evolve?

D.M.: At the beginning of my artistic career I was a figurative painter and a drawer, oriented towards a material ‘deconstruction’ of the human being. I used to study the effect of light projected onto works. Depending on the inclination of the light beam, an illusory three-dimensional effect could be achieved through the presence or the absence of matter. A video installation of this process often accompanied my works.

I knew that technology had to play an important role in my research, and brush and canvas were no longer sufficient in ‘representing’ my time. Limiting myself to painting a human being in front of a computer, for example, wouldn’t have made me a truly ‘contemporary artist’, witness of my present.

That was undeniably a time of crisis, but also a time of research and study; marked by the first digital terrestrial transmissions. I remember that during the run-in phase of this system, the images were often distorted by pixels, due to the poor reception of the digital signal by the terrestrial transmitter. I realised that my works had to be affected by the same interference, an error, an unexpected datum given by the technology. My works had to interact with these digital instruments, until becoming one thing.

The research went in this direction, so much that new energies came out of depression. I felt renewed, someone else: light, video clips, software specially designed for me to reproduce digital interference, digital prints… Just to mention some of the ingredients that allow me to create my works.

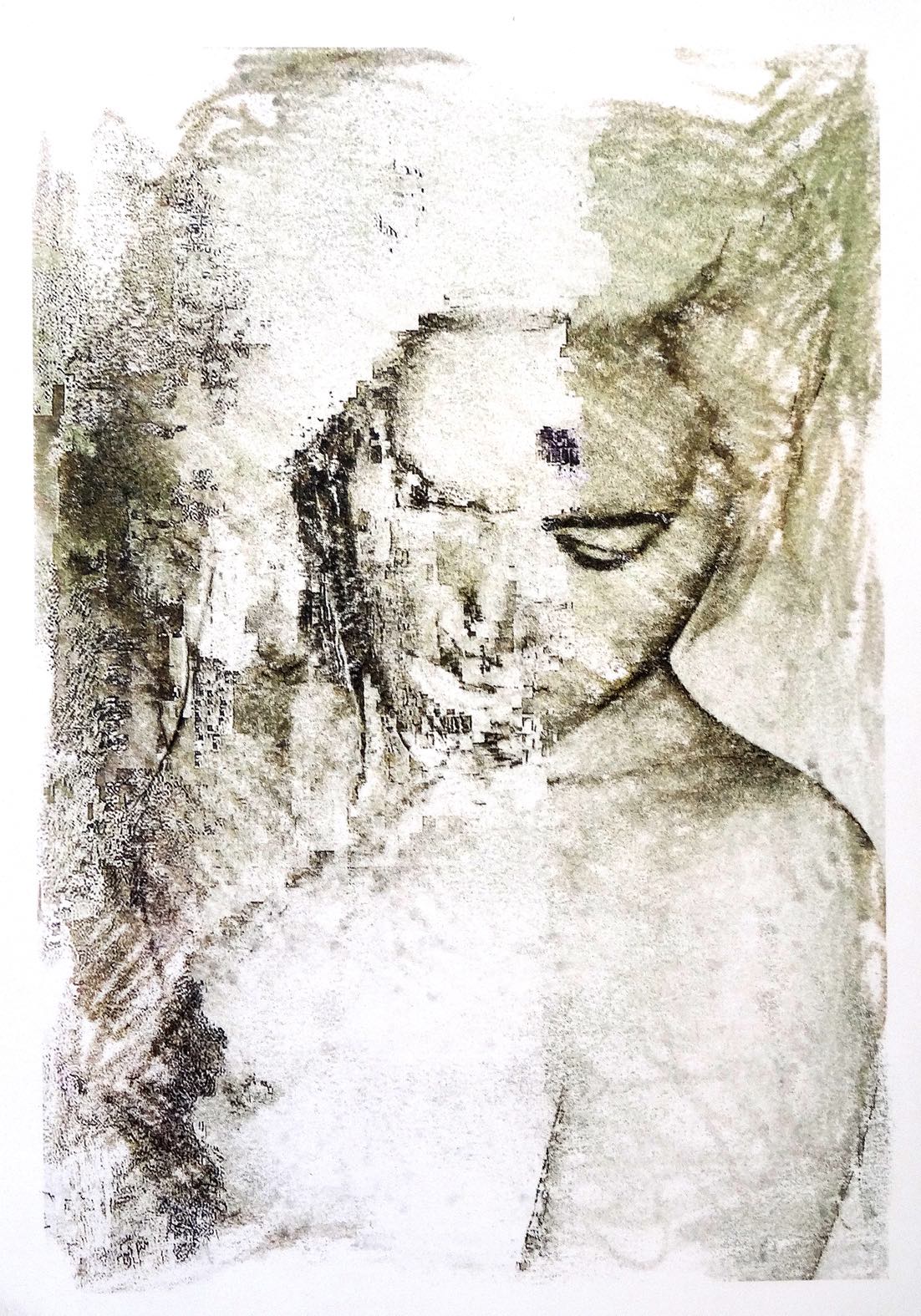

Though, there is a paradox: I still remain anchored to the past, I am still an ‘old’ drawer and painter, as I deliberately continue to produce the ‘negative films’ of my works getting my hands dirty with colour. But then, precisely in order to testify the occurrence of this mutation, the initial artworks ‘die’ during the process of making, remaining nevertheless trapped in a thin digital film.

C.F.: I found extremely fascinating the ambivalent contribution of the “Machine” in your process of making: meant to be automatically predictable, thus it introduce a variable of “unexpected”. How is this “error” likely to turn or to add beauty to a handmade works?

D.M.: I wondered that too. But the first time I saw the result I was amazed like a child: it wasn’t expected at all. It was so fascinating, probably because it was not predicted. I deliberately wanted to investigate the error in the coding system of the digital images, because they were so apparently perfect that they looked real. An interference destroyed an almost certain image, which rested indeed on something extremely fragile. It is a bit of a reminder of our time, where the boundary between the real and the sensory, hence between the material and the ephemeral, is very blurred. I wanted to trap that moment, perhaps transitory, but which is meant to invite the viewer to pause for a moment and reflect on himself. The error has created an unexpected event, which – speaking of everyday life – is perhaps that aspect we aim to avoid as much as possible, even if it’s always just around the corner. The ‘unexpected variable’ of my works is perhaps synonymous of human intuition, the only way of thinking transversally and not vertically like a machine. I see it as a beautiful form of provocation against today’s society, where rationalisation is increasingly taking over. I believe art should investigate and question the present, even annoy, and push people to reflect. But above all, art should tell the truth. Honestly, the kind of appreciation I prefer, when it comes to my works, is when people tell me there is something disturbing, not ‘beautiful’.

C.F.: All your titles recall a key concept in your poetic, the idea of ephemerality: in particular, in your last projects Fade and Digital Interferences, you destroyed the physical initial portraits, which survive only in its digital deconstruction. The tangible work proof to be essential but transitory, while technology attributes an endless series of possibilities, a new unpredicted Aura. This is also a (positive) reflection about our time…

D.M.: There is no doubt that the historical moment we are living, corresponds to an epochal change in which we will see an increasing intrusion of digitalisation: not only in the production and communication processes, but it will increasingly touch the human sphere. This is something we can’t stop, but only accept.

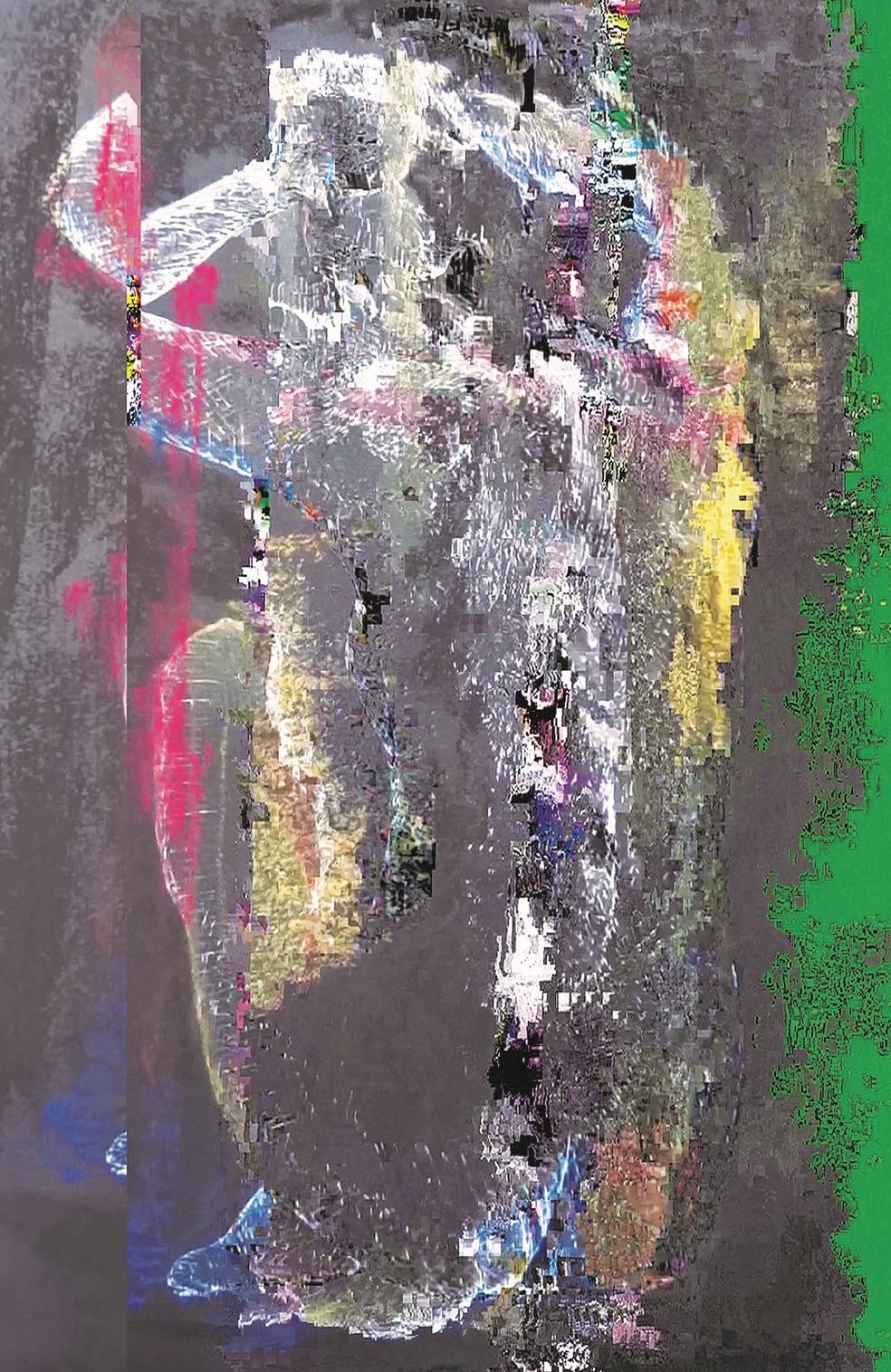

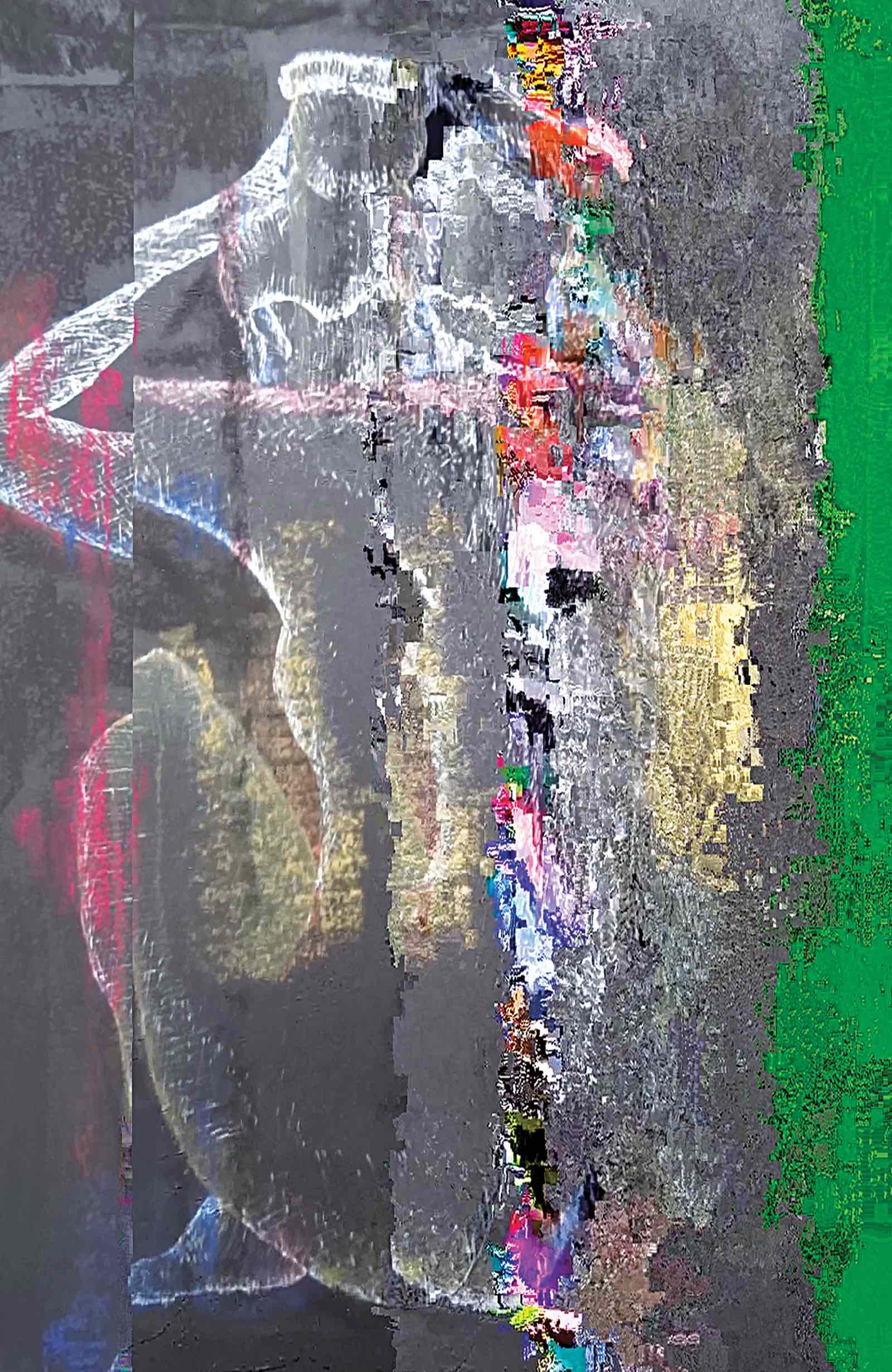

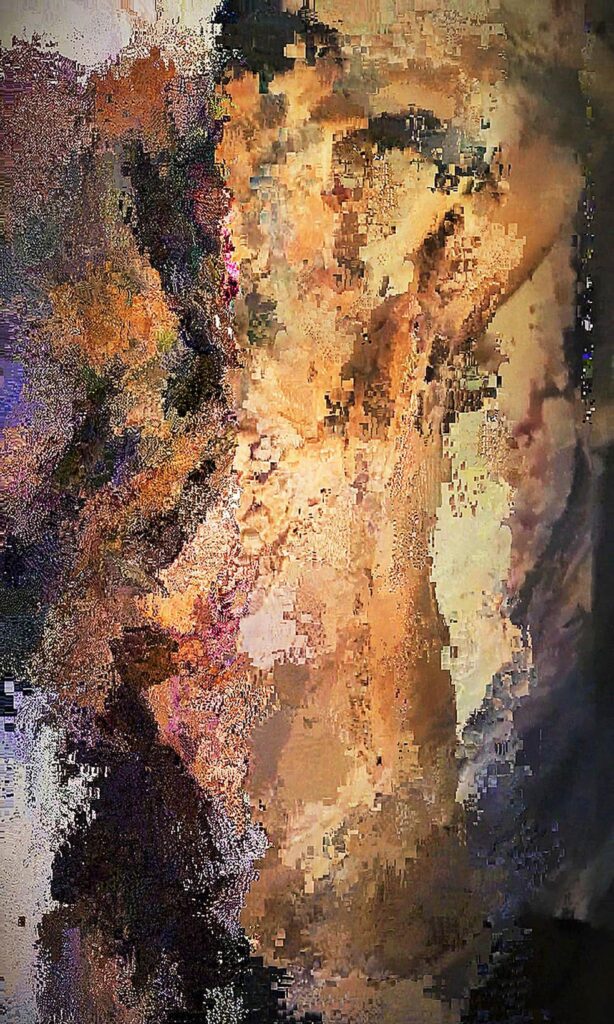

Digital interferences series. Print on PET. Courtesy the artist

In my artistic research, a fragment comparable to a ‘frame’ of a film, in short, is the final result of my work. A process that could run infinitely, so as to obtain unlimited facets of the same identical portrait, which can be always different, yet turning in something divergent from the departing point.

Perhaps there is a warning, a risk in letting this present overflowing: the incapacity of understanding when we have to stop and grasp what we can feel and still true, real; otherwise the danger of losing it for good could be too high. The positive side, if perceived in my artistic message, is that, trapped in a thin digital film, there is still a fragment of experience. The machine has not yet definitively replaced man. Let’s not forget that.

C.F.: Every artworks you produce, almost as living beings, seems to go through a personal, structured process of self-maturation, made of physicality, light, until the opening over infinite possibilities. Does this poietic process reflect your own idea of experience?

D.M.: Yes, of course. It is clear that I prefer the representation of human beings, not really for the difficulty of execution or to make the subject portrayed closest as possible to reality. Instead, I think it’s a matter of curiosity and need to catch or perceive something of themselves through the other.

All the people in my works shared – more and some less intimately – a part of their life with me, as family members, life partners, models, friends. When I work on their expressions, faces or bodies, I think of us. It is pleasant at times, while sometimes when I see old pictures I relive the nostalgia of a memory, or even the anger, if something hasn’t been serenely accepted. In every cases there was an exchange, an experience with these individuals, so that I represent a fragment of something, shared solely with them.

Thus, my artworks narrate stories: they reflect something that has been experienced, which is now a memory. I believe that an artist, in my field or in another, cannot omit himself/herself in the artistic production: consciously or not, there is always a biographical element that has to rise to the surface. If someone has no past experience to share or doesn’t dare look deep inside, it’s way better to give up.

C.F.: Throughout your career you have always shown a preference for institutional projects: what do you wish will come next?

D.M.: My preference for institutions is not a secret: I had the chance to work with art centres, foundations and municipalities. I have always felt comfortable with the professionalism of the various cultural actors I have dealt with. When the socio-cultural aspect takes over, everyone goes in the same direction, everything is easier. In these contexts, I never had to distort myself as an artist or even to modify my projects, which is definitely the main risk of commercial environments.

For me, it is essential sharing my research with people whose ultimate goal is to make the transmission of knowledge possible. I don’t want to sound hypocritical, by saying that money is not important: for me it is important as investment in my researches. How else would I produce them? I just believe that the ultimate goal of Art is not to make money.

I like this idea, that one day my work could reach a larger audience and the intrinsic message in my poetic could survive me as an artist. Afterall, the fact that some of my works are now present in some public contexts it’s a reward for all my efforts.