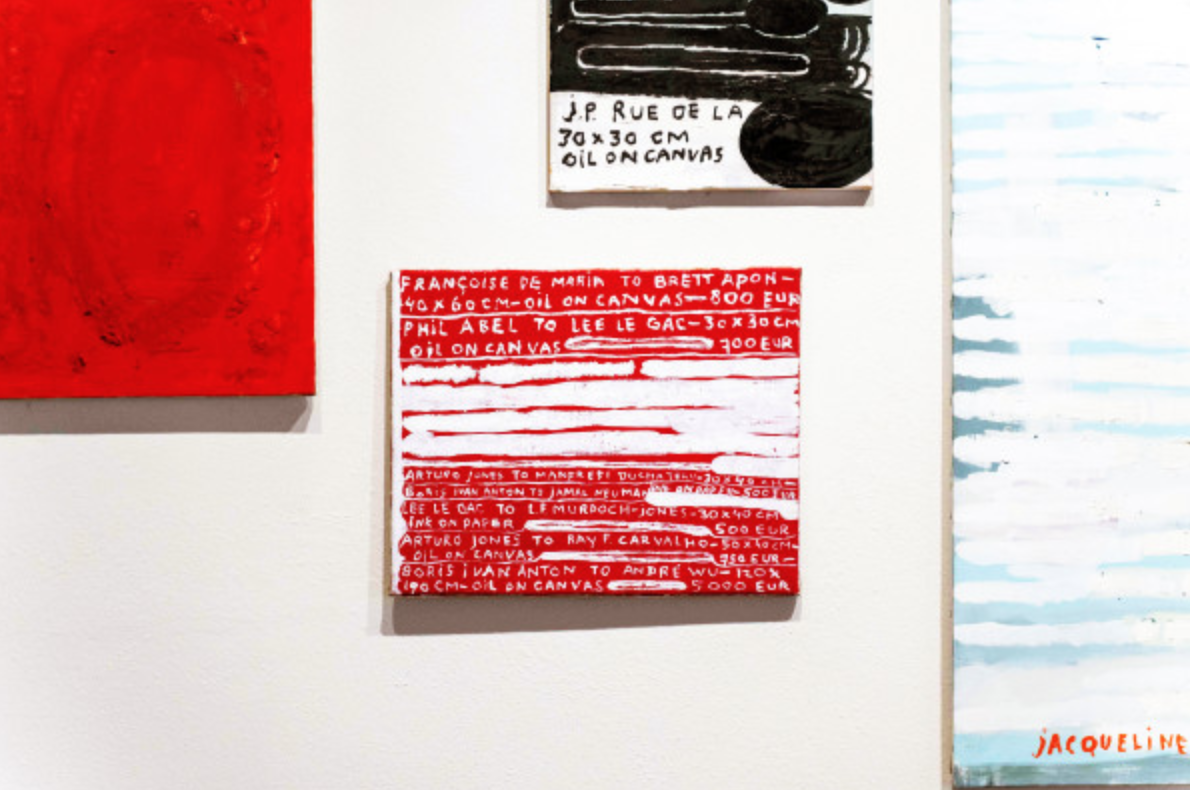

We met Jacqueline Peeters at her exhibition Unsold Paintings at Zazà Ramen Sake Bar and Restaurant (Milan, Italy). Based on a shared vision with Brendan Becht, founder of Zazà Ramen, and its artistic program, the exhibition presents a selection of Peeters’ pictorial works, set up like a typical 17th century paintings collections: every wall is namely covered by the paintings, arranged by colour combinations and dimensions, rather than a chronological order.

The intimate setting of the restaurant makes the visitors feel in genuine connection with Peeters’ works of art and the journey into her imagination and her intimate world is led with an unedited spontaneity. The leading point of this journey is an open criticism to the art system and its economical laws. Above all, all the paintings express the artist’s inability to become part of it. From the disappointment of her inability to create a network with art galleries and with the right people, arise the fantasies of creating an exhibition of unsold paintings. Here, this “frustration” against the art system, is transformed into a creative boost and becomes the theme of the artist’s research itself.

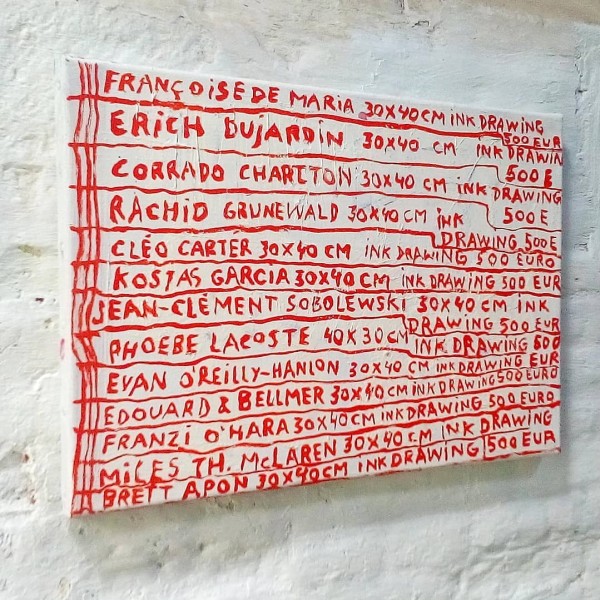

In Jacqueline Peeters’ works, words play a central role. In order to create this imaginary exhibition of unsold paintings, the artist paints on canvas titles, dimensions, dates, techniques and prices. In this way she also becomes a poet, who creates fictitious names for the non-existing art galleries. What is important to keep in mind is that this disappointment is never expressed like a passive frustration, but it’s a kind of boost for Jacqueline Peeters’ artistic research, which is always characterized by a thread of irony: Jacqueline Peeters plays a game with the art world. What she finds out, at the end of the game, is the awareness of being a good painter and the fact that she doesn’t have to demonstrate it, she doesn’t have to bow to the art market’s rules or please art collectors.

Our interview with Jacqueline Peeters concerns the role of art in contemporary society, failure and the freedom brought through failure. We loved talking with Jacqueline because what can be observed at first sight is the fact that, starting from the admission of inability, begins a deep journey into creativity and artistic research, always led with biting wit. That is what art is about, but life too.

Laura Ferrini

Laura Ferrini: What’s the role of art in contemporary society, in your opinion?

Jacqueline Peeters:To me, art is a source of pleasure. It offers beauty and consolation, a means for reflection and understanding, and an opportunity for identification. I suppose art can play similar roles in society, or for specific communities. I recently made paintings of coffins. Many people share my fears about the impact of the corona pandemic on their lives and on society. But I must say that I sometimes get bored with art that ticks all the right boxes: gender, race, social class, migration, feminism, queering, diversity… It is often so unimaginative.

L.F.: Which are the main themes of your artistic research?

J.P: I want to make breathtakingly beautiful and moving paintings. However, most of the time I do not succeed. So perhaps my art is about failure. Twenty-five years ago I started making invitation cards and posters for fictitious exhibitions at non-existing galleries – a scream for attention and at the same time a way to mask my unsuccessful career as an artist. This “marketing ploy” became the subject of my work and the work of art itself.

I also liked inventing names for my galleries. Perhaps I am a failed poet, who is trying to amend things by writing words on paintings. I am a mender.

L.F.: Your exhibition Unsold Paintings is set up in Zazà Ramen Restaurant & Sake Bar. Do you prefer to exhibit your works in unconventional places despite art galleries? Do you think that exhibitions in unconventional places could make art more accessible and reach many more people?

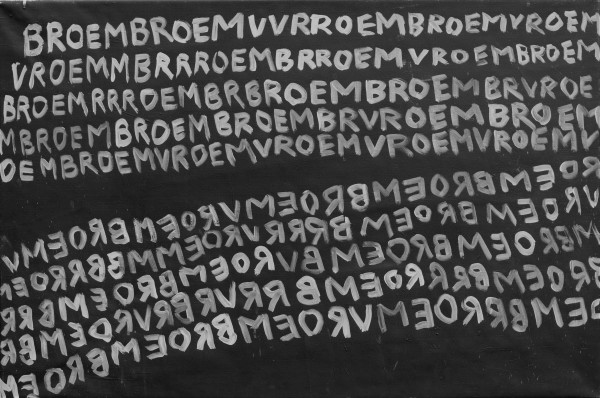

J.P: I really like the idea of exhibiting in a restaurant, where people enjoy food while discussing my work. It is the unpretentiousness that I like. Even if people don’t know the slightest about art, or are not in the least interested in art, there is always something that may trigger a thought in them that they never had before. One of my paintings at Zazà only contains the words “broem broem”, the sound of a car engine. Perhaps one of the diners will read it aloud, pretend to go somewhere, or even make steering movements!

When I was in art school, I painted Indonesian dishes on paper tablecloths, so I share my passion for art and food with Brendan.

L.F.: During your artistic research you have stopped painting and then started again. Is there a particular reason why? Is there a leitmotiv brought through your production? Has something changed?

J.P: Why did I stop painting? I was fed up with begging people to come and visit my studio. The disappointment. Arrgh! What also put me off was the fact that my financial situation was directly dependent on whether someone liked my paintings. At some point I asked myself: When I am forty, do I still want to be dependent on government grants or the judgement of other people? I decided that it was better to earn money with a ‘real’ job.

When I started to paint again after a long hiatus, I wondered whether I should burden my heirs with an ever-growing legacy of unsaleable art works. So I decided to make art that can be easily disassembled – by pinning pieces of fabric and paper onto a canvas, instead of applying paint. I thought it would be easier for my heirs to dispose of materials pinned onto canvas than of paintings with carefully applied brushstrokes.

But I missed the mixing of colours, the layeredness. I started to document all my unsold paintings. If my son wants to get rid of his mum’s paintings, he can do so without feeling guilty.

L.F.: The fil rouge of your Unsold Paintings is a form of criticism directed to the art market and its economical rules. In your career did a specific episode make you feel the urge to express the concept through your art?

J.P: I would not use the word ‘criticism’. I prefer the term ‘mockery’. I realise that the art market is a model of supply and demand. I do not only mock the art world but also myself. For my inability to take part, for my vanity, for begging for attention.

There was a time when I used to rush down the stairs of my Brussels apartment to check what the postman had brought that morning. Letters with my name and address on them: Jacqueline Peeters, Rue de Parme. I decided that in order to be successful I should be more commercial and take on an alias. The family name Peeters is very common in Belgium and the Netherlands. I thought Jacqueline de Parme, Rue Peeters would be more apt for a famous artist. Around that time I also made my first Unsold Painting, playing with the idea that such a conceptual excursion would attract the attention of the art world.

L.F.: Do you think that it is possible to be out of the world of art and to be able to sell paintings in your own way, maybe using a digital market?

J.P: I suppose one still needs a network of people who admire and promote your work. Being a smooth talker, a clever seducer, a likeable, young and beautiful person may also be assets.

L.F.: Your scream against the art market is just the leading point of your artistic research. In other works, such as Fecit (1994-2019), you’ve expressed the theme of a 20-year-long journey in depth. Have you discovered something that you think could be important, or useful for other human beings?

J.P: Mmm. Instead of a scream against the art market it would say it is a scream for attention. The idea behind the Fecit work was: if I do not succeed in selling my paintings, why make any new ones at all? Why not just paint the same painting over and over again, and only add a new date.

I am a good painter and what I have learned is that I don’t have to demonstrate that I am a good painter. I do not have to bow to the art market’s rules or please art collectors.

L.F.: Are there any artists who have influenced your production in a very significant way?

J.P: I admire Vuillard for his intimacy, Picasso for his boldness, Van Gogh for his brushstrokes, Manet for the shades of white and black, Matisse for his playfulness. I sometimes borrow titles from other artists, for example, I made a painting of a fountain which I called Fountain at Baden-Baden, which is the title of a work by Max Beckmann. I am now working on a painting called La Mulâtresse, after Matisse, about my coloured ancestors.

I should also pay tribute to Jan Dibbets, one of my tutors in art school, who once said to me: “Don’t think you’re a wunderkind, Peeters, get to work!”